Android Reverse Engineering Guide

Its openness makes Android a favorable environment for reverse engineers. However, dealing with both Java and native code can make things more complicated at times. In the following chapter, we'll look at some peculiarities of Android reversing and OS-specific tools as processes.

In comparison to "the other" mobile OS, Android offers some big advantages to reverse engineers. Because Android is open source, you can study the source code of the Android Open Source Project (AOSP), modify the OS and its standard tools in any way you want. Even on standard retail devices, it is easily possible to do things like activating developer mode and sideloading apps without jumping through many hoops. From the powerful tools shipping with the SDK, to the wide range of available reverse engineering tools, there's a lot of niceties to make your life easier.

However, there's also a few Android-specific challenges. For example, you'll need to deal with both Java bytecode and native code. Java Native Interface (JNI) is sometimes used on purpose to confuse reverse engineers. Developers sometimes use the native layer to "hide" data and functionality, or may structure their apps such that execution frequently jumps between the two layers. This can complicate things for reverse engineers (to be fair, there might also be legitimate reasons for using JNI, such as improving performance or supporting legacy code).

You'll need a working knowledge about both the Java-based Android environment and the Linux OS and Kernel that forms the basis of Android - or better yet, know all these components inside out. Plus, they need the right toolset to deal with both native code and bytecode running inside the Java virtual machine.

Note that in the following sections we'll use the OWASP Mobile Testing Guide Crackmes [1] as examples for demonstrating various reverse engineering techniques, so expect partial and full spoilers. We encourage you to have a crack at the challenges yourself before reading on!

What You Need

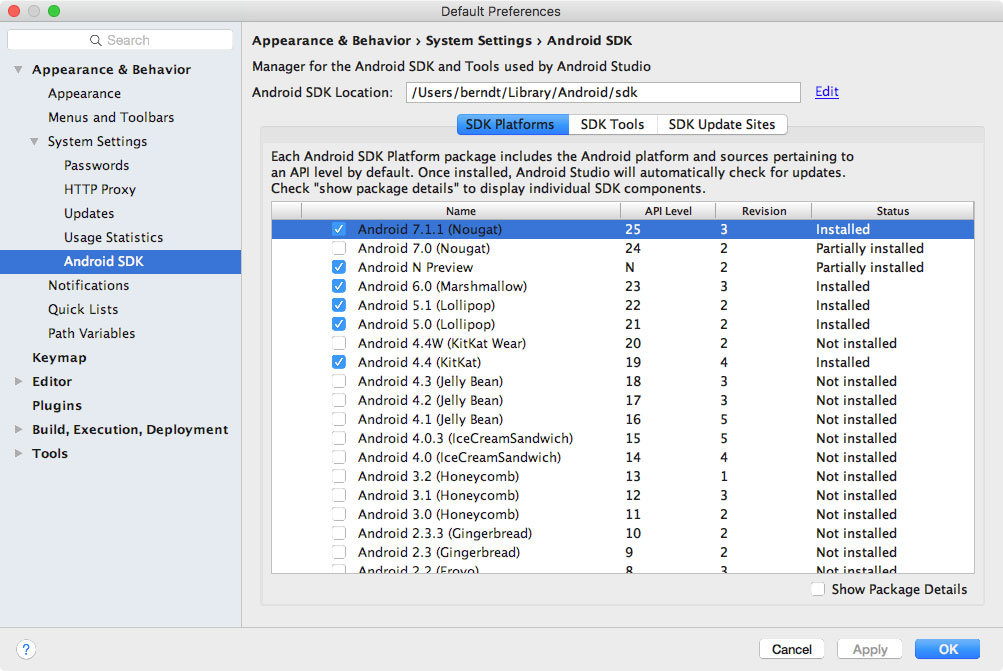

At the very least, you'll need Android Studio [2], which comes with the Android SDK, platform tools and emulator, as well as a manager app for managing the various SDK versions and framework components. With Android Studio, you also get an SDK Manager app that lets you install the Android SDK tools and manage SDKs for various API levels, as well as the emulator and an AVD Manager application to create emulator images. Make sure that the following is installed on your system:

The newest SDK Tools and SDK Platform-Tools packages. These packages include the Android Debugging Bridge (ADB) client as well as other tools that interface with the Android platform. In general, these tools are backward-compatible, so you need only one version of those installed.

The Android NDK. This is the Native Development Kit that contains prebuilt toolchains for cross-compiling native code for different architectures.

In addition to the SDK and NDK, you'll also something to make Java bytecode more human-friendly. Fortunately, Java decompilers generally deal well with Android bytecode. Popular free decompilers include JD [3], Jad [4], Proycon [5] and CFR [6]. For convenience, we have packed some of these decompilers into our apkx wrapper script [7]. This script completely automates the process of extracting Java code from release APK files and makes it easy to experiment with different backends (we'll also use it in some of the examples below).

Other than that, it's really a matter of preference and budget. A ton of free and commercial disassemblers, decompilers, and frameworks with different strengths and weaknesses exist - we'll cover some of them below.

Setting up the Android SDK

Local Android SDK installations are managed through Android Studio. Create an empty project in Android Studio and select "Tools->Android->SDK Manager" to open the SDK Manager GUI. The "SDK Platforms" tab lets you install SDKs for multiple API levels. Recent API levels are:

- API 21: Android 5.0

- API 22: Android 5.1

- API 23: Android 6.0

- API 24: Android 7.0

- API 25: Android 7.1

- API 26: Android O Developer Preview

Depending on your OS, installed SDKs are found at the following location:

Windows:

C:\Users\<username>\AppData\Local\Android\sdk

MacOS:

/Users/<username>/Library/Android/sdk

Note: On Linux, you'll need pick your own SDK location. Common locations are /opt, /srv, and /usr/local.

Setting up the Android NDK

The Android NDK contains prebuilt versions of the native compiler and toolchain. Traditionally, both the GCC and Clang compilers were supported, but active support for GCC ended with revision 14 of the NDK. What's the right version to use depends on both the device architecture and host OS. The prebuilt toolchains are located in the toolchainsdirectory of the NDK, which contains one subdirectory per architecture.

| Architecture | Toolchain name |

|---|---|

| ARM-based | arm-linux-androideabi-<gcc-version> |

| x86-based | x86-<gcc-version> |

| MIPS-based | mipsel-linux-android-<gcc-version> |

| ARM64-based | aarch64-linux-android-<gcc-version> |

| X86-64-based | x86_64-<gcc-version> |

| MIPS64-based | mips64el-linux-android-<gcc-version> |

In addition to the picking the right architecture, you need to specify the correct sysroot for the native API level you want to target. The sysroot is a directory that contains the system headers and libraries for your target. Available native APIs vary by Android API level. Possible sysroots for respective Android API levels reside under $NDK/platforms/, each API-level directory contains subdirectories for the various CPUs and architectures.

One possibility to set up the build system is exporting the compiler path and necessary flags as environment variables. To make things easier however, the NDK allows you to create a so-called standalone toolchain - a "temporary" toolchain that incorporates the required settings.

To set up a standalone toolchain, download the latest stable version of the NDK [8]. Extract the ZIP file, change into the NDK root directory and run the following command:

$ ./build/tools/make_standalone_toolchain.py --arch arm --api 24 --install-dir /tmp/android-7-toolchain

This creates a standalone toolchain for Android 7.0 in the directory /tmp/android-7-toolchain. For convenience, you can export an environment variable that points to your toolchain directory - we'll be using this in the examples later. Run the following command, or add it to your .bash_profile or other startup script.

$ export TOOLCHAIN=/tmp/android-7-toolchain

Building a Reverse Engineering Environment For Free

With a little effort you can build a reasonable GUI-powered reverse engineering environment for free.

For navigating the decompiled sources we recommend using IntelliJ [9], a relatively light-weight IDE that works great for browsing code and allows for basic on-device debugging of the decompiled apps. However, if you prefer something that's clunky, slow and complicated to use, Eclipse [10] is the right IDE for you (note: This piece of advice is based on the author's personal bias).

If you don’t mind looking at Smali instead of Java code, you can use the smalidea plugin for IntelliJ for debugging on the device [11]. Smalidea supports single-stepping through the bytecode, identifier renaming and watches for non-named registers, which makes it much more powerful than a JD + IntelliJ setup.

APKTool [12] is a popular free tool that can extract and disassemble resources directly from the APK archive and disassemble Java bytecode to Smali format (Smali/Baksmali is an assembler/disassembler for the Dex format. It's also Icelandic for "Assembler/Disassembler"). APKTool allows you to reassemble the package, which is useful for patching and applying changes to the Manifest.

More elaborate tasks such as program analysis and automated de-obfuscation can be achieved with open source reverse engineering frameworks such as Radare2 [13] and Angr [14]. You'll find usage examples for many of these free tools and frameworks throughout the guide.

Commercial Tools

Even though it is possible to work with a completely free setup, you might want to consider investing in commercial tools. The main advantage of these tools is convenience: They come with a nice GUI, lots of automation, and end user support. If you earn your daily bread as a reverse engineer, this will save you a lot of time.

JEB

JEB [15], a commercial decompiler, packs all the functionality needed for static and dynamic analysis of Android apps into an all-in-one package, is reasonably reliable and you get quick support. It has a built-in debugger, which allows for an efficient workflow – setting breakpoints directly in the decompiled (and annotated sources) is invaluable, especially when dealing with ProGuard-obfuscated bytecode. Of course convenience like this doesn’t come cheap - and since version 2.0 JEB has changed from a traditional licensing model to a subscription-based one, so you'll need to pay a monthly fee to use it.

IDA Pro

IDA Pro [16] understands ARM, MIPS and of course Intel ELF binaries, plus it can deal with Java bytecode. It also comes with debuggers for both Java applications and native processes. With its capable disassembler and powerful scripting and extension capabilities, IDA Pro works great for static analysis of native programs and libraries. However, the static analysis facilities it offers for Java code are somewhat basic – you get the Smali disassembly but not much more. There’s no navigating the package and class structure, and some things (such as renaming classes) can’t be done which can make working with more complex Java apps a bit tedious.

Reverse Engineering

Reverse engineering is the process of taking an app apart to find out how it works. You can do this by examining the compiled app (static analysis), observing the app during runtime (dynamic analysis), or a combination of both.

Statically Analyzing Java Code

Unless some nasty, tool-breaking anti-decompilation tricks have been applied, Java bytecode can be converted back into source code without too many problems. We'll be using UnCrackable App for Android Level 1 in the following examples, so download it if you haven't already. First, let's install the app on a device or emulator and run it to see what the crackme is about.

$ wget https://github.com/OWASP/owasp-mstg/raw/master/Crackmes/Android/Level_01/UnCrackable-Level1.apk

$ adb install UnCrackable-Level1.apk

Seems like we're expected to find some kind of secret code!

Most likely, we're looking for a secret string stored somewhere inside the app, so the next logical step is to take a look inside. First, unzip the APK file and have a look at the content.

$ unzip UnCrackable-Level1.apk -d UnCrackable-Level1

Archive: UnCrackable-Level1.apk

inflating: UnCrackable-Level1/AndroidManifest.xml

inflating: UnCrackable-Level1/res/layout/activity_main.xml

inflating: UnCrackable-Level1/res/menu/menu_main.xml

extracting: UnCrackable-Level1/res/mipmap-hdpi-v4/ic_launcher.png

extracting: UnCrackable-Level1/res/mipmap-mdpi-v4/ic_launcher.png

extracting: UnCrackable-Level1/res/mipmap-xhdpi-v4/ic_launcher.png

extracting: UnCrackable-Level1/res/mipmap-xxhdpi-v4/ic_launcher.png

extracting: UnCrackable-Level1/res/mipmap-xxxhdpi-v4/ic_launcher.png

extracting: UnCrackable-Level1/resources.arsc

inflating: UnCrackable-Level1/classes.dex

inflating: UnCrackable-Level1/META-INF/MANIFEST.MF

inflating: UnCrackable-Level1/META-INF/CERT.SF

inflating: UnCrackable-Level1/META-INF/CERT.RSA

In the standard case, all the Java bytecode and data related to the app is contained in a file named classes.dex in the app root directory. This file adheres to the Dalvik Executable Format (DEX), an Android-specific way of packaging Java programs. Most Java decompilers expect plain class files or JARs as input, so you need to convert the classes.dex file into a JAR first. This can be done using dex2jar or enjarify.

Once you have a JAR file, you can use any number of free decompilers to produce Java code. In this example, we'll use CFR as our decompiler of choice. CFR is under active development, and brand-new releases are made available regularly on the author's website [6]. Conveniently, CFR has been released under a MIT license, which means that it can be used freely for any purposes, even though its source code is not currently available.

The easiest way to run CFR is through apkx, which also packages dex2jar and automates the extracting, conversion and decompilation steps. Install it as follows:

$ git clone https://github.com/b-mueller/apkx

$ cd apkx

$ sudo ./install.sh

This should copy apkx to /usr/local/bin. Run it on UnCrackable-Level1.apk:

$ apkx UnCrackable-Level1.apk

Extracting UnCrackable-Level1.apk to UnCrackable-Level1

Converting: classes.dex -> classes.jar (dex2jar)

dex2jar UnCrackable-Level1/classes.dex -> UnCrackable-Level1/classes.jar

Decompiling to UnCrackable-Level1/src (cfr)

You should now find the decompiled sources in the directory Uncrackable-Level1/src. To view the sources, a simple text editor (preferably with syntax highlighting) is fine, but loading the code into a Java IDE makes navigation easier. Let's import the code into IntelliJ, which also gets us on-device debugging functionality as a bonus.

Open IntelliJ and select "Android" as the project type in the left tab of the "New Project" dialog. Enter "Uncrackable1" as the application name and "vantagepoint.sg" as the company name. This results in the package name "sg.vantagepoint.uncrackable1", which matches the original package name. Using a matching package name is important if you want to attach the debugger to the running app later on, as Intellij uses the package name to identify the correct process.

In the next dialog, pick any API number - we don't want to actually compile the project, so it really doesn't matter. Click "next" and choose "Add no Activity", then click "finish".

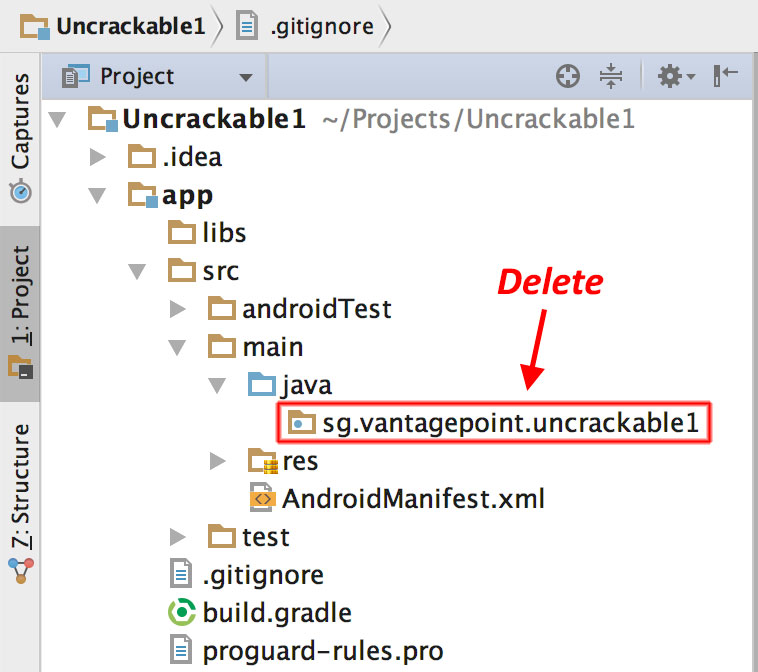

Once the project is created, expand the "1: Project" view on the left and navigate to the folder app/src/main/java. Right-click and delete the default package "sg.vantagepoint.uncrackable1" created by IntelliJ.

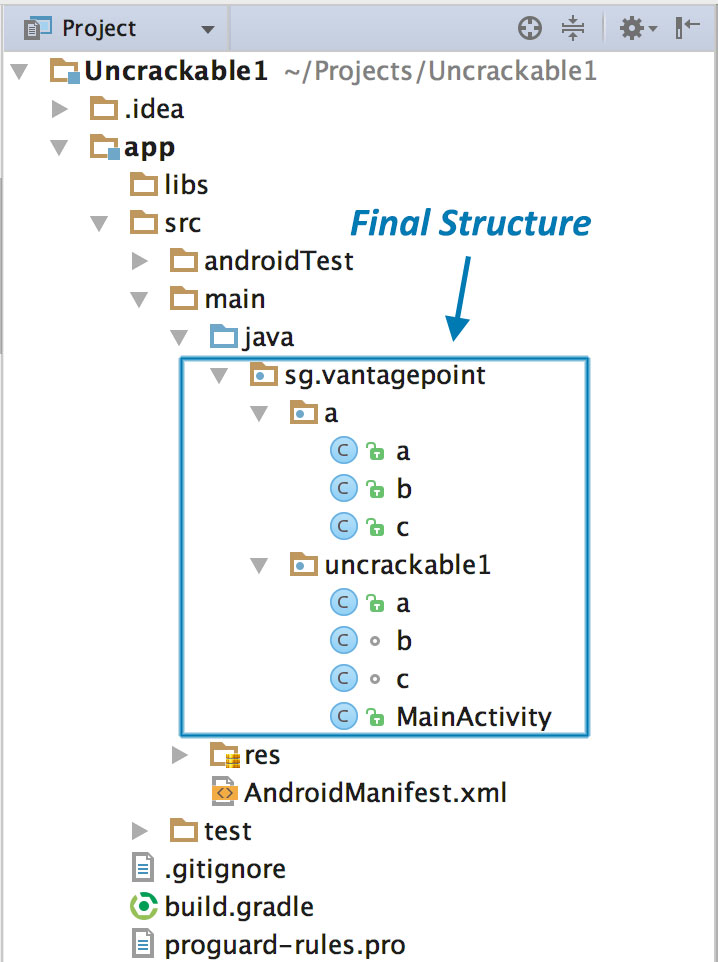

Now, open the Uncrackable-Level1/src directory in a file browser and drag the sg directory into the now empty Java folder in the IntelliJ project view (hold the "alt" key to copy the folder instead of moving it).

You'll end up with a structure that resembles the original Android Studio project from which the app was built.

As soon as IntelliJ is done indexing the code, you can browse it just like any normal Java project. Note that many of the decompiled packages, classes and methods have weird one-letter names... this is because the bytecode has been "minified" with ProGuard at build time. This is a a basic type of obfuscation that makes the bytecode a bit more difficult to read, but with a fairly simple app like this one it won't cause you much of a headache - however, when analyzing a more complex app, it can get quite annoying.

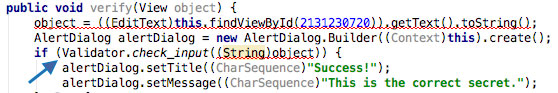

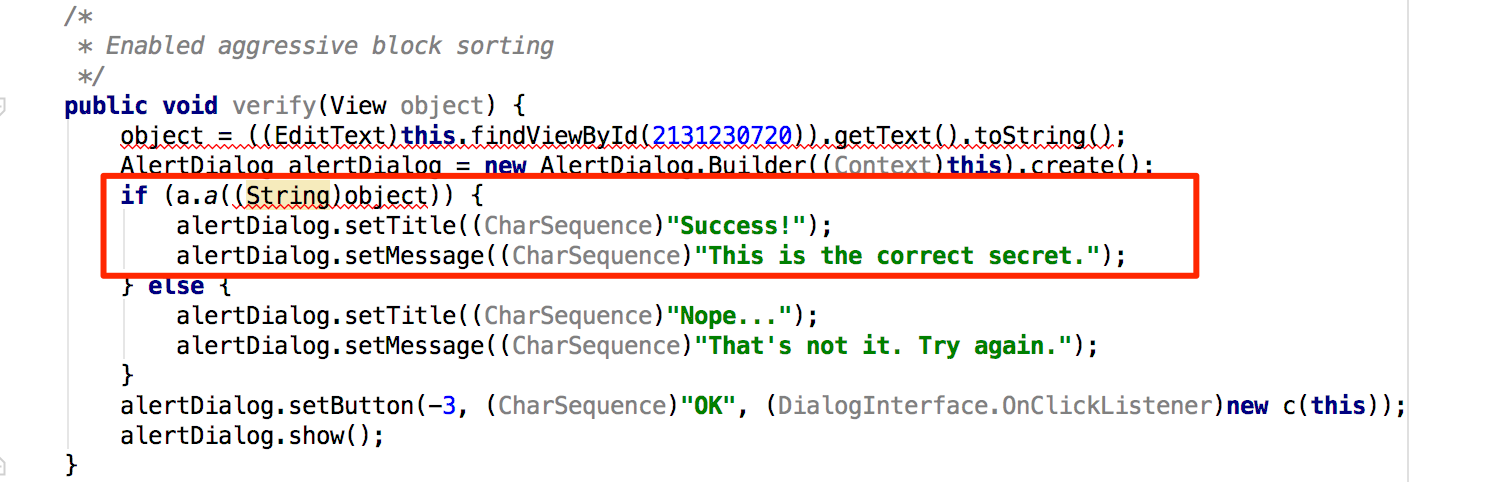

A good practice to follow when analyzing obfuscated code is to annotate names of classes, methods and other identifiers as you go along. Open the MainActivity class in the package sg.vantagepoint.a. The method verify is what's called when you tap on the "verify" button. This method passes the user input to a static method called a.a, which returns a boolean value. It seems plausible that a.a is responsible for verifying whether the text entered by the user is valid or not, so we'll start refactoring the code to reflect this.

Right-click the class name - the first a in a.a - and select Refactor->Rename from the drop-down menu (or press Shift-F6). Change the class name to something that makes more sense given what you know about the class so far. For example, you could call it "Validator" (you can always revise the name later as you learn more about the class). a.a now becomes Validator.a. Follow the same procedure to rename the static method a to check_input.

Congratulations - you just learned the fundamentals of static analysis! It is all about theorizing, annotating, and gradually revising theories about the analyzed program, until you understand it completely - or at least, well enough for whatever you want to achieve.

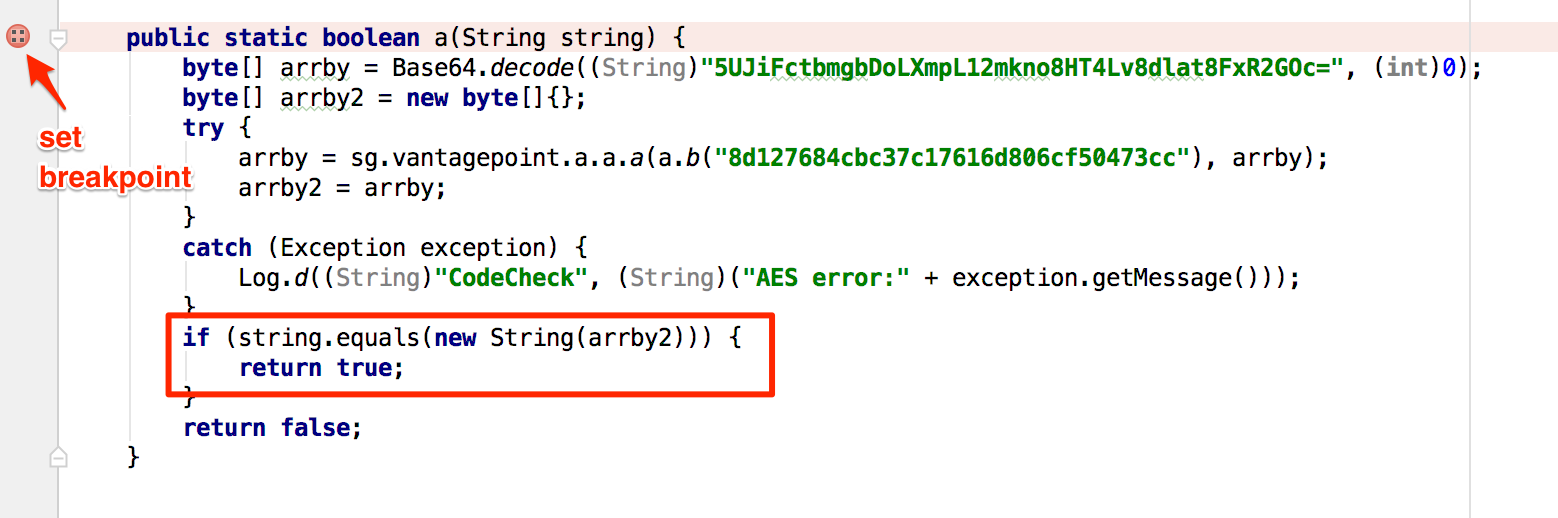

Next, ctrl+click (or command+click on Mac) on the check_input method. This takes you to the method definition. The decompiled method looks as follows:

public static boolean check_input(String string) {

byte[] arrby = Base64.decode((String)"5UJiFctbmgbDoLXmpL12mkno8HT4Lv8dlat8FxR2GOc=", (int)0);

byte[] arrby2 = new byte[]{};

try {

arrby = sg.vantagepoint.a.a.a(Validator.b("8d127684cbc37c17616d806cf50473cc"), arrby);

arrby2 = arrby;

}sa

catch (Exception exception) {

Log.d((String)"CodeCheck", (String)("AES error:" + exception.getMessage()));

}

if (string.equals(new String(arrby2))) {

return true;

}

return false;

}

So, we have a base64-encoded String that's passed to a function named a in the package sg.vantagepoint.a.a (again everything is called a) along with something that looks suspiciously like a hex-encoded encryption key (16 hex bytes = 128bit, a common key length). What exactly does this particular a do? Ctrl-click it to find out.

public class a {

public static byte[] a(byte[] object, byte[] arrby) {

object = new SecretKeySpec((byte[])object, "AES/ECB/PKCS7Padding");

Cipher cipher = Cipher.getInstance("AES");

cipher.init(2, (Key)object);

return cipher.doFinal(arrby);

}

}

Now we are getting somewhere: It's simply standard AES-ECB. Looks like the base64 string stored in arrby1 in check_input is a ciphertext, which is decrypted using 128bit AES, and then compared to the user input. As a bonus task, try to decrypt the extracted ciphertext and get the secret value!

An alternative (and faster) way of getting the decrypted string is by adding a bit of dynamic analysis into the mix - we'll revisit UnCrackable Level 1 later to show how to do this, so don't delete the project yet!

Statically Analyzing Native Code

Dalvik and ART both support the Java Native Interface (JNI), which defines defines a way for Java code to interact with native code written in C/C++. Just like on other Linux-based operating systes, native code is packaged into ELF dynamic libraries ("*.so"), which are then loaded by the Android app during runtime using the System.load method.

Android JNI functions consist of native code compiled into Linux ELF libraries. It's pretty much standard Linux fare. However, instead of relying on widely used C libraries such as glibc, Android binaries are built against a custom libc named Bionic [17]. Bionic adds support for important Android-specific services such as system properties and logging, and is not fully POSIX-compatible.

Download HelloWorld-JNI.apk from the OWASP MSTG repository and, optionally, install and run it on your emulator or Android device.

$ wget HelloWord-JNI.apk

$ adb install HelloWord-JNI.apk

This app is not exactly spectacular: All it does is show a label with the text "Hello from C++". In fact, this is the default app Android generates when you create a new project with C/C++ support - enough however to show the basic principles of how JNI calls work.

Decompile the APK with apkx. This extract the source code into the HelloWorld/src directory.

$ wget https://github.com/OWASP/owasp-mstg/blob/master/OMTG-Files/03_Examples/01_Android/01_HelloWorld-JNI/HelloWord-JNI.apk

$ apkx HelloWord-JNI.apk

Extracting HelloWord-JNI.apk to HelloWord-JNI

Converting: classes.dex -> classes.jar (dex2jar)

dex2jar HelloWord-JNI/classes.dex -> HelloWord-JNI/classes.jar

The MainActivity is found in the file MainActivity.java. The "Hello World" text view is populated in the onCreate() method:

public class MainActivity

extends AppCompatActivity {

static {

System.loadLibrary("native-lib");

}

@Override

protected void onCreate(Bundle bundle) {

super.onCreate(bundle);

this.setContentView(2130968603);

((TextView)this.findViewById(2131427422)).setText((CharSequence)this.stringFromJNI());

}

public native String stringFromJNI();

}

}

Note the declaration of public native String stringFromJNI at the bottom. The native keyword informs the Java compiler that the implementation for this method is provided in a native language. The corresponding function is resolved during runtime. Of course, this only works if a native library is loaded that exports a global symbol with the expected signature. This signature is composed of the package name, class name and method name. In our case for example, this means that the programmer must have implemented the following C or C++ function:

JNIEXPORT jstring JNICALL Java_sg_vantagepoint_helloworld_MainActivity_stringFromJNI(JNIEnv *env, jobject)

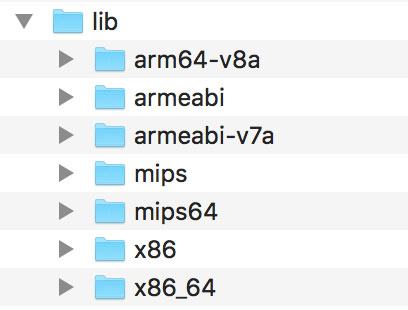

So where is the native implementation of this function? If you look into the lib directory of the APK archive, you'll see a total of eight subdirectories named after different processor architectures. Each of this directories contains a version of the native library libnative-lib.so, compiled for the processor architecture in question. When System.loadLibrary is called, the loader selects the correct version based on what device the app is running on.

Following the naming convention mentioned above, we can expect the library to export a symbol named Java_sg_vantagepoint_helloworld_MainActivity_stringFromJNI. On Linux systems, you can retrieve the list of symbols using readelf (included in GNU binutils) or nm. On Mac OS, the same can be achieved with the greadelf tool, which you can install via Macports or Homebrew. The following example uses greadelf:

$ greadelf -W -s libnative-lib.so | grep Java

3: 00004e49 112 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 11 Java_sg_vantagepoint_helloworld_MainActivity_stringFromJNI

This is the native function that gets eventually executed when the stringFromJNI native method is called.

To disassemble the code, you can load libnative-lib.so into any disassembler that understands ELF binaries (i.e. every disassembler in existence). If the app ships with binaries for different architectures, you can theoretically pick the architecture you're most familiar with, as long as the disassembler knows how to deal with it. Each version is compiled from the same source and implements exactly the same functionality. However, if you're planning to debug the library on a live device later, it's usually wise to pick an ARM build.

To support both older and newer ARM processors, Android apps ship with multple ARM builds compiled for different Application Binary Interface (ABI) versions. The ABI defines how the application's machine code is supposed to interact with the system at runtime. The following ABIs are supported:

- armeabi: ABI is for ARM-based CPUs that support at least the ARMv5TE instruction set.

- armeabi-v7a: This ABI extends armeabi to include several CPU instruction set extensions.

- arm64-v8a: ABI for ARMv8-based CPUs that support AArch64, the new 64-bit ARM architecture.

Most disassemblers will be able to deal with any of those architectures. Below, we'll be viewing the armeabi-v7a version in IDA Pro. It is located in lib/armeabi-v7a/libnative-lib.so. If you don't own an IDA Pro license, you can do the same thing with demo or evaluation version available on the Hex-Rays website [13].

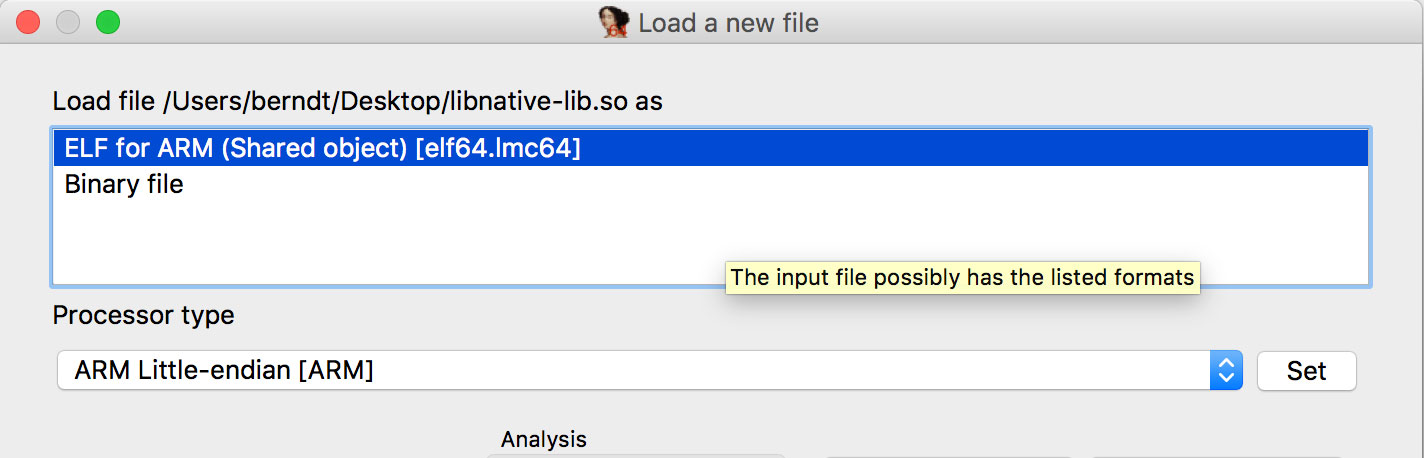

Open the file in IDA Pro. In the "Load new file" dialog, choose "ELF for ARM (Shared Object)" as the file type (IDA should detect this automatically), and "ARM Little-Endian" as the processor type.

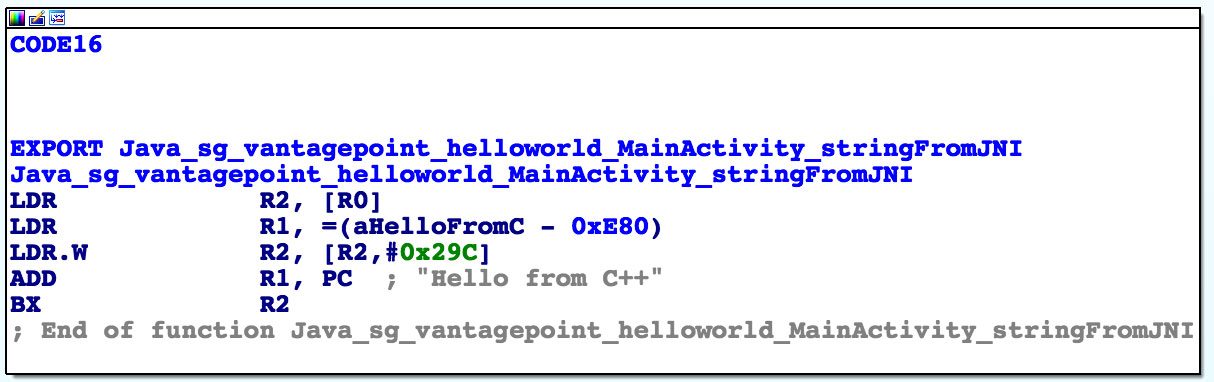

Once the file is open, click into the "Functions" window on the left and press Alt+t to open the search dialog. Enter "java" and hit enter. This should highlight the Java_sg_vantagepoint_helloworld_MainActivity_stringFromJNI function. Double-click it to jump to its address in the disassembly Window. "Ida View-A" should now show the disassembly of the function.

Not a lot of code there, but let's analyze it. The first thing we need to know is that the first argument passed to every JNI is a JNI interface pointer. An interface pointer is a pointer to a pointer. This pointer points to a function table - an array of even more pointers, each of which points to a JNI interface function (is your head spinning yet?). The function table is initialized by the Java VM, and allows the native function to interact with the Java environment.

With that in mind, let's have a look at each line of assembly code.

LDR R2, [R0]

Remember - the first argument (located in R0) is a pointer to the JNI function table pointer. The LDR instruction loads this function table pointer into R2.

LDR R1, =aHelloFromC

This instruction loads the pc-relative offset of the string "Hello from C++" into R1. Note that this string is located directly after the end of the function block at offset 0xe84. The addressing relative to the program counter allows the code to run independent of its position in memory.

LDR.W R2, [R2, #0x29C]

This instruction loads the function pointer from offset 0x29C into the JNI function pointer table into R2. This happens to be the NewStringUTF function. You can look the list of function pointers in jni.h, which is included in the Android NDK. The function prototype looks as follows:

jstring (*NewStringUTF)(JNIEnv*, const char*);

The function expects two arguments: The JNIEnv pointer (already in R0) and a String pointer. Next, the current value of PC is added to R1, resulting in the absolute address of the static string "Hello from C++" (PC + offset).

ADD R1, PC

Finally, the program executes a branch instruction to the NewStringUTF function pointer loaded into R2:

BX R2

When this function returns, R0 contains a pointer to the newly constructed UTF string. This is the final return value, so R0 is left unchanged and the function ends.

Debugging and Tracing

So far, we've been using static analysis techniques without ever running our target apps. In the real world - especially when reversing more complex apps or malware - you'll find that pure static analysis is very difficult. Observing and manipulating an app during runtime makes it much, much easier to decipher its behavior. Next, we'll have a look at dynamic analysis methods that help you do just that.

Android apps support two different types of debugging: Java-runtime-level debugging using Java Debug Wire Protocol (JDWP) and Linux/Unix-style ptrace-based debugging on the native layer, both of which are valuable for reverse engineers.

Activating Developer Options

Since Android 4.2, the "Developer options" submenu is hidden by default in the Settings app. To activate it, you need to tap the "Build number" section of the "About phone" view 7 times. Note that the location of the build number field can vary slightly on different devices - for example, on LG Phones, it is found under "About phone > Software information" instead. Once you have done this, "Developer options" will be shown at bottom of the Settings menu. Once developer options are activated, debugging can be enabled with the "USB debugging" switch.

Debugging Release Apps

Dalvik and ART support the Java Debug Wire Protocol (JDWP), a protocol used for communication between the debugger and the Java virtual machine (VM) which it debugs. JDWP is a standard debugging protocol that is supported by all command line tools and Java IDEs, including JDB, JEB, IntelliJ and Eclipse. Android's implementation of JDWP also includes hooks for supporting extra features implemented by the Dalvik Debug Monitor Server (DDMS).

Using a JDWP debugger allows you to step through Java code, set breakpoints on Java methods, and inspect and modify local and instance variables. You'll be using a JDWP debugger most of the time when debugging "normal" Android apps that don't do a lot of calls into native libraries.

In the following section, we'll show how to solve UnCrackable App for Android Level 1 using JDB only. Note that this is not an efficient way to solve this crackme - you can do it much faster using Frida and other methods, which we'll introduce later in the guide. It serves however well an an introduction to the capabilities of the Java debugger.

Repackaging

Every debugger-enabled process runs an extra thread for handling JDWP protocol packets. this thread is started only for apps that have the android:debuggable="true" tag set in their Manifest file's <application> element. This is typically the configuration on Android devices shipped to end users.

When reverse engineering apps, you'll often only have access to the release build of the target app. Release builds are not meant to be debugged - after all, that's what debug builds are for. If the system property ro.debuggable set to "0", Android disallows both JDWP and native debugging of release builds, and although this is easy to bypass, you'll still likely encounter some limitations, such as a lack of line breakpoints. Nevertheless, even an imperfect debugger is still an invaluable tool - being able to inspect the runtime state of a program makes it a lot easier to understand what's going on.

To "convert" a release build release into a debuggable build, you need to modify a flag in the app's Manifest file. This modification breaks the code signature, so you'll also have to re-sign the the altered APK archive.

To do this, you first need a code signing certificate. If you have built a project in Android Studio before, the IDE has already created a debug keystore and certificate in $HOME/.android/debug.keystore. The default password for this keystore is "android" and the key is named "androiddebugkey".

The Java standard distibution includes keytool for managing keystores and certificates. You can create your own signing certificate and key and add it to the debug keystore as follows:

$ keytool -genkey -v -keystore ~/.android/debug.keystore -alias signkey -keyalg RSA -keysize 2048 -validity 20000

With a certificate available, you can now repackage the app using the following steps. Note that the Android Studio build tools directory must be in path for this to work - it is located at [SDK-Path]/build-tools/[version]. The zipalign and apksigner tools are found in this directory. Repackage UnCrackable-Level1.apk as follows:

- Use apktool to unpack the app and decode AndroidManifest.xml:

$ apktool d --no-src UnCrackable-Level1.apk

- Add android:debuggable = “true” to the manifest using a text editor:

<application android:allowBackup="true" android:debuggable="true" android:icon="@drawable/ic_launcher" android:label="@string/app_name" android:name="com.xxx.xxx.xxx" android:theme="@style/AppTheme">

- Repackage and sign the APK.

$ cd UnCrackable-Level1

$ apktool b

$ zipalign -v 4 dist/UnCrackable-Level1.apk ../UnCrackable-Repackaged.apk

$ cd ..

$ apksigner sign --ks ~/.android/debug.keystore --ks-key-alias signkey UnCrackable-Repackaged.apk

Note: If you experience JRE compatibility issues with apksigner, you can use jarsigner instead. Note that in this case, zipalign is called after signing.

$ jarsigner -verbose -keystore ~/.android/debug.keystore UnCrackable-Repackaged.apk signkey

$ zipalign -v 4 dist/UnCrackable-Level1.apk ../UnCrackable-Repackaged.apk

- Reinstall the app:

$ adb install UnCrackable-Repackaged.apk

The 'Wait For Debugger' Feature

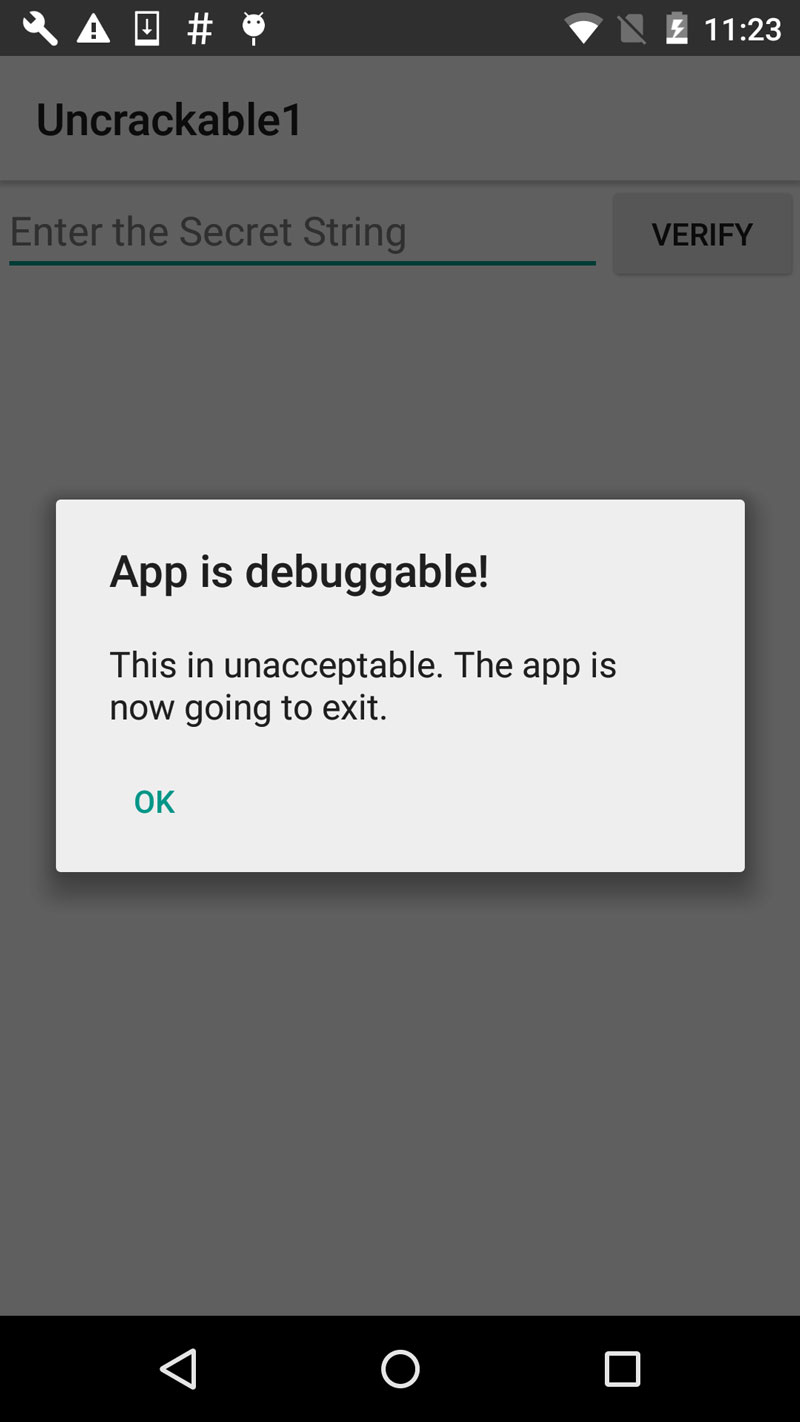

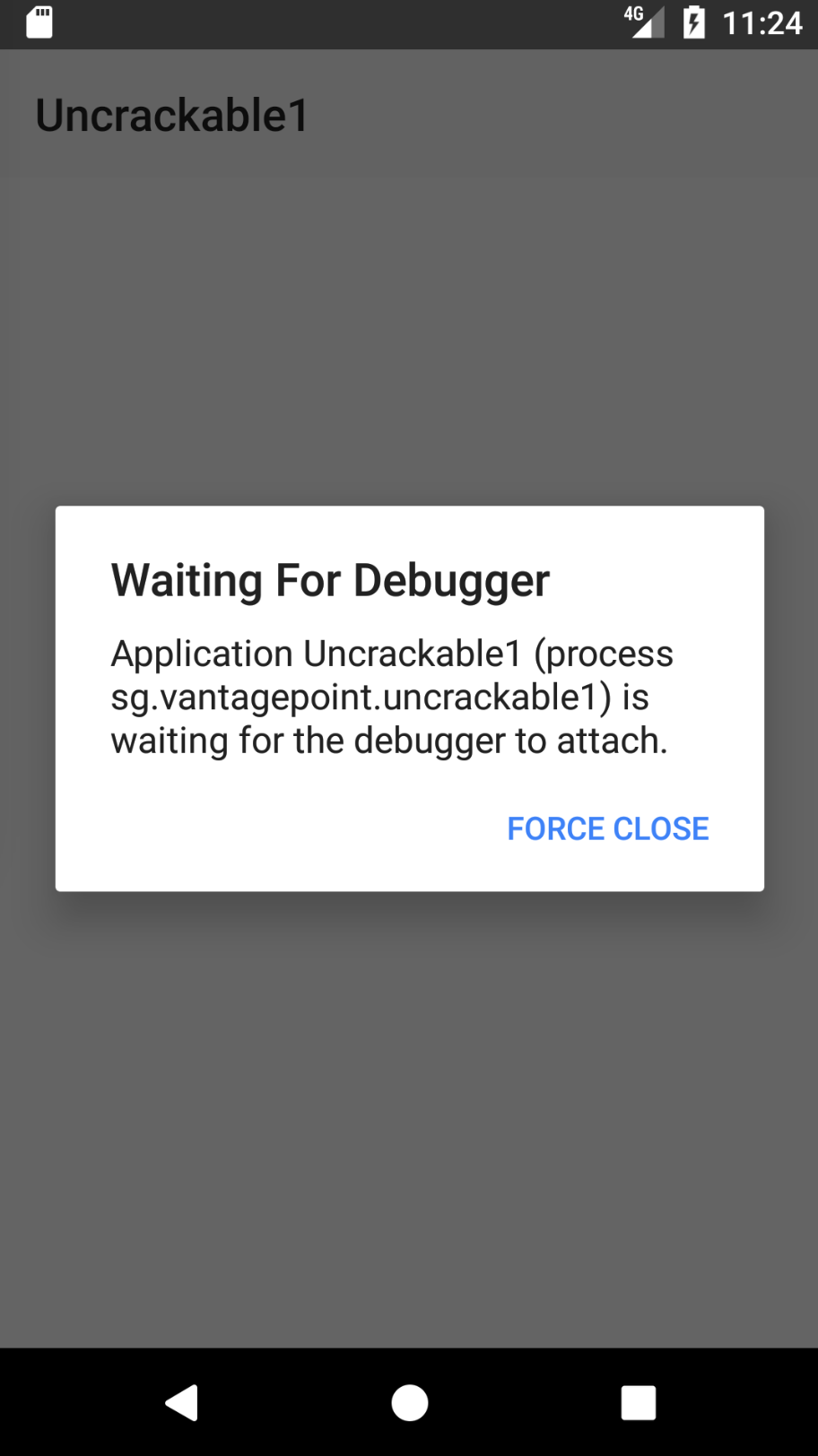

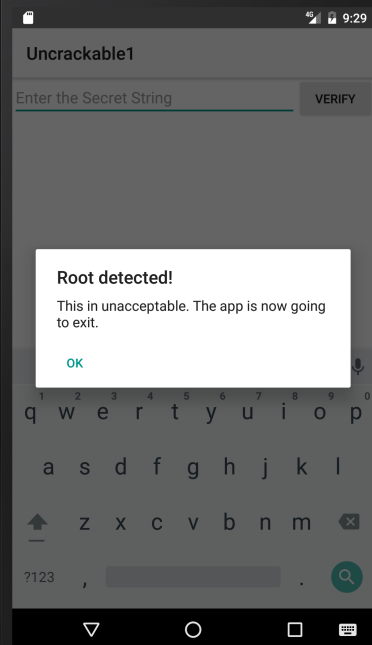

UnCrackable App is not stupid: It notices that it has been run in debuggable mode and reacts by shutting down. A modal dialog is shown immediately and the crackme terminates once you tap the OK button.

Fortunately, Android's Developer options contain the useful "Wait for Debugger" feature, which allows you to automatically suspend a selected app doing startup until a JDWP debugger connects. By using this feature, you can connect the debugger before the detection mechanism runs, and trace, debug and deactivate that mechanism. It's really an unfair advantage, but on the other hand, reverse engineers never play fair!

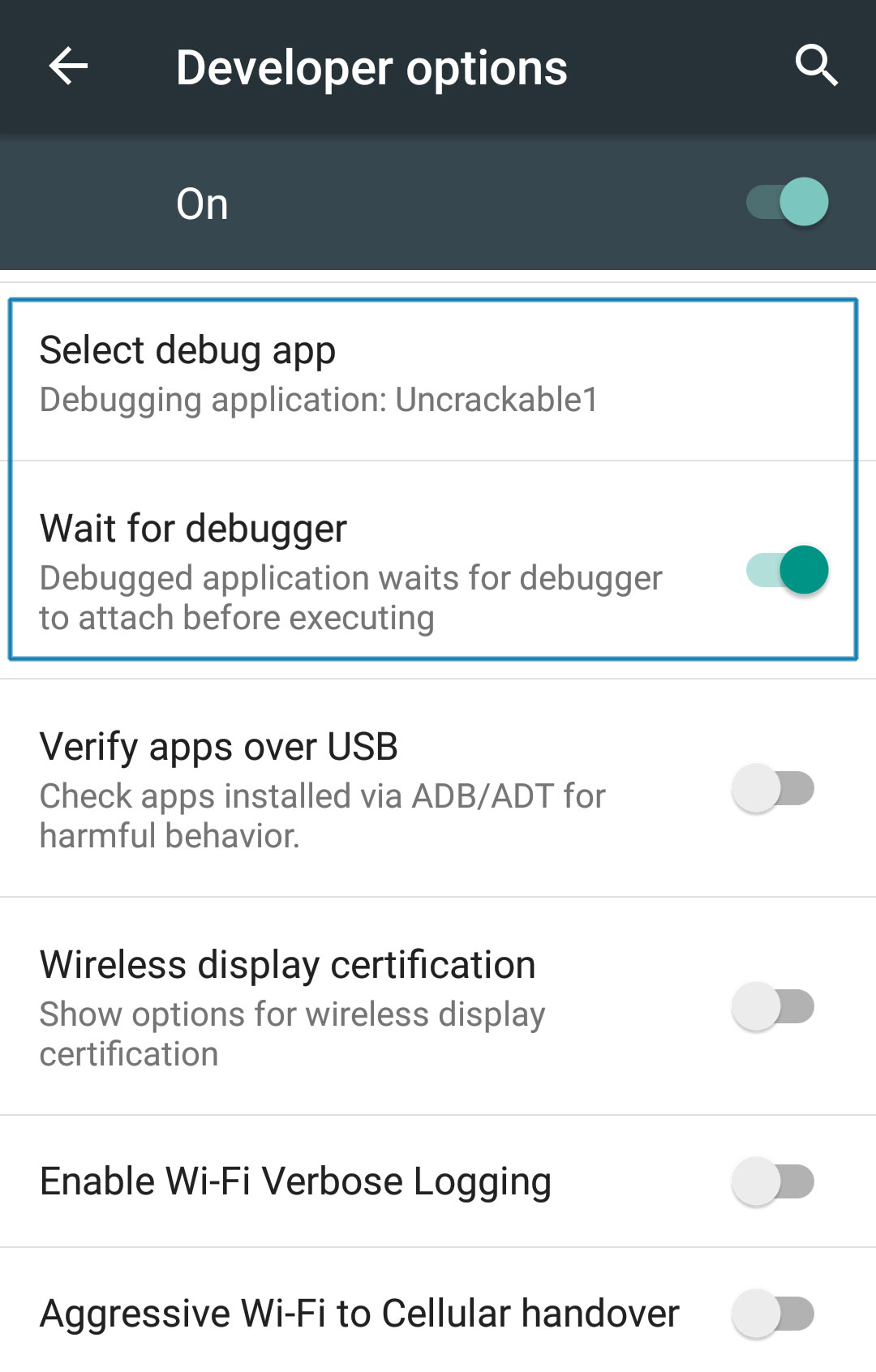

In the Developer Settings, pick Uncrackable1 as the debugging application and activate the "Wait for Debugger" switch.

Note: Even with ro.debuggable set to 1 in default.prop, an app won't show up in the "debug app" list unless the android:debuggable flag is set to true in the Manifest.

The Android Debug Bridge

The adb command line tool, which ships with the Android SDK, bridges the gap between your local development environment and a connected Android device. Commonly you'll debug apps on the emulator or on a device connected via USB. Use the adb devices command to list the currently connected devices.

$ adb devices

List of devices attached

090c285c0b97f748 device

The adb jdwp command lists the process ids of all debuggable processes running on the connected device (i.e., processes hosting a JDWP transport). With the adb forward command, you can open a listening socket on your host machine and forward TCP connections to this socket to the JDWP transport of a chosen process.

$ adb jdwp

12167

$ adb forward tcp:7777 jdwp:12167

We're now ready to attach JDB. Attaching the debugger however causes the app to resume, which is something we don't want. Rather, we'd like to keep it suspended so we can do some exploration first. To prevent the process from resuming, we pipe the suspend command into jdb:

$ { echo "suspend"; cat; } | jdb -attach localhost:7777

Initializing jdb ...

> All threads suspended.

>

We are now attached to the suspended process and ready to go ahead with jdb commands. Entering ? prints the complete list of. Unfortunately, the Android VM doesn't support all available JDWP features. For example, the redefine command, which would let us redefine the code for a class - a potentially very useful feature - is not supported. Another important restriction is that line breakpoints won't work, because the release bytecode doesn't contain line information. Method breakpoints do work however. Useful commands that work include:

- classes: List all loaded classes

- class / method / fields

: Print details about a class and list its method and fields - locals: print local variables in current stack frame

- print / dump

: print information about an object - stop in

: set a method breakpoint - clear

: remove a method breakpoint - set

= : assign new value to field/variable/array element

Let's revisit the decompiled code of UnCrackable App Level 1 and think about possible solutions. A good approach would be to suspend the app at a state where the secret string is stored in a variable in plain text so we can retrieve it. Unfortunately, we won't get that far unless we deal with the root / tampering detection first.

By reviewing the code, we can gather that the method sg.vantagepoint.uncrackable1.MainActivity.a is responsible for displaying the "This in unacceptable..." message box. This method hooks the "OK" button to a class that implements the OnClickListener interface. The onClick event handler on the "OK" button is what actually terminates the app. To prevent the user from simply cancelling the dialog, the setCancelable method is called.

private void a(final String title) {

final AlertDialog create = new AlertDialog$Builder((Context)this).create();

create.setTitle((CharSequence)title);

create.setMessage((CharSequence)"This in unacceptable. The app is now going to exit.");

create.setButton(-3, (CharSequence)"OK", (DialogInterface$OnClickListener)new b(this));

create.setCancelable(false);

create.show();

}

We can bypass this with a little runtime tampering. With the app still suspended, set a method breakpoint on android.app.Dialog.setCancelable and resume the app.

> stop in android.app.Dialog.setCancelable

Set breakpoint android.app.Dialog.setCancelable

> resume

All threads resumed.

>

Breakpoint hit: "thread=main", android.app.Dialog.setCancelable(), line=1,110 bci=0

main[1]

The app is now suspended at the first instruction of the setCancelable method. You can print the arguments passed to setCancelable using the locals command (note that the arguments are incorrectly shown under "local variables").

main[1] locals

Method arguments:

Local variables:

flag = true

In this case, setCancelable(true) was called, so this can't be the call we're looking for. Resume the process using the resume command.

main[1] resume

Breakpoint hit: "thread=main", android.app.Dialog.setCancelable(), line=1,110 bci=0

main[1] locals

flag = false

We've now hit a call to setCancelable with the argument false. Set the variable to true with the set command and resume.

main[1] set flag = true

flag = true = true

main[1] resume

Repeat this process, setting flag to true each time the breakpoint is hit, until the alert box is finally displayed (the breakpoint will hit 5 or 6 times). The alert box should now be cancelable! Tap anywhere next to the box and it will close without terminating the app.

Now that the anti-tampering is out of the way we're ready to extract the secret string! In the "static analysis" section, we saw that the string is decrypted using AES, and then compared with the string entered into the messagebox. The method equals of the java.lang.String class is used to compare the input string with the secret. Set a method breakpoint on java.lang.String.equals, enter any text into the edit field, and tap the "verify" button. Once the breakpoint hits, you can read the method argument with the using the locals command.

> stop in java.lang.String.equals

Set breakpoint java.lang.String.equals

>

Breakpoint hit: "thread=main", java.lang.String.equals(), line=639 bci=2

main[1] locals

Method arguments:

Local variables:

other = "radiusGravity"

main[1] cont

Breakpoint hit: "thread=main", java.lang.String.equals(), line=639 bci=2

main[1] locals

Method arguments:

Local variables:

other = "I want to believe"

main[1] cont

This is the plaintext string we are looking for!

Debugging Using an IDE

A pretty neat trick is setting up a project in an IDE with the decompiled sources, which allows you to set method breakpoints directly in the source code. In most cases, you should be able single-step through the app, and inspect the state of variables through the GUI. The experience won't be perfect - it's not the original source code after all, so you can't set line breakpoints and sometimes things will simply not work correctly. Then again, reversing code is never easy, and being able to efficiently navigate and debug plain old Java code is a pretty convenient way of doing it, so it's usually worth giving it a shot. A similar method has been described in the NetSPI blog [18].

In order to debug an app from the decompiled source code, you should first create your Android project and copy the decompiled java sources into the source folder as described above at "Statically Analyzing Java Code" part. Set the debug app (in this tutorial it is Uncrackable1) and make sure you turned on "Wait For Deugger" switch from "Developer Options".

Once you tap the Uncrackable app icon from the launcher, it will get suspended in "wait for a debugger" mode.

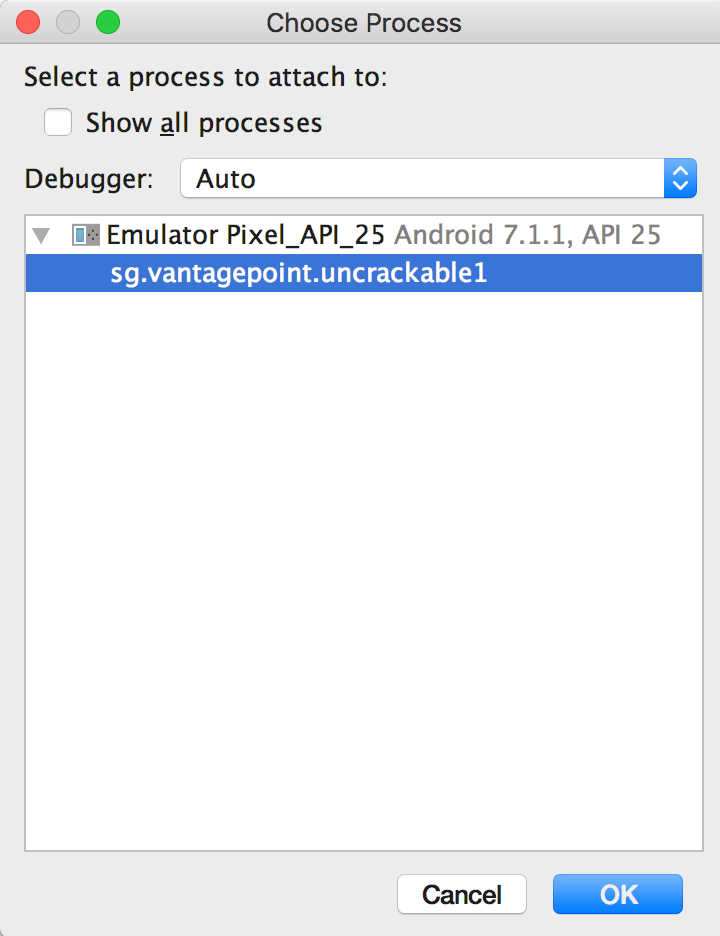

Now you can set breakpoints and attach to the Uncrackable1 app process using the "Attach Debugger" button on the toolbar.

Note that only method breakpoints work when debugging an app from decompiled sources. Once a method breakpoint is hit, you will get the chance to single step throughout the method execution.

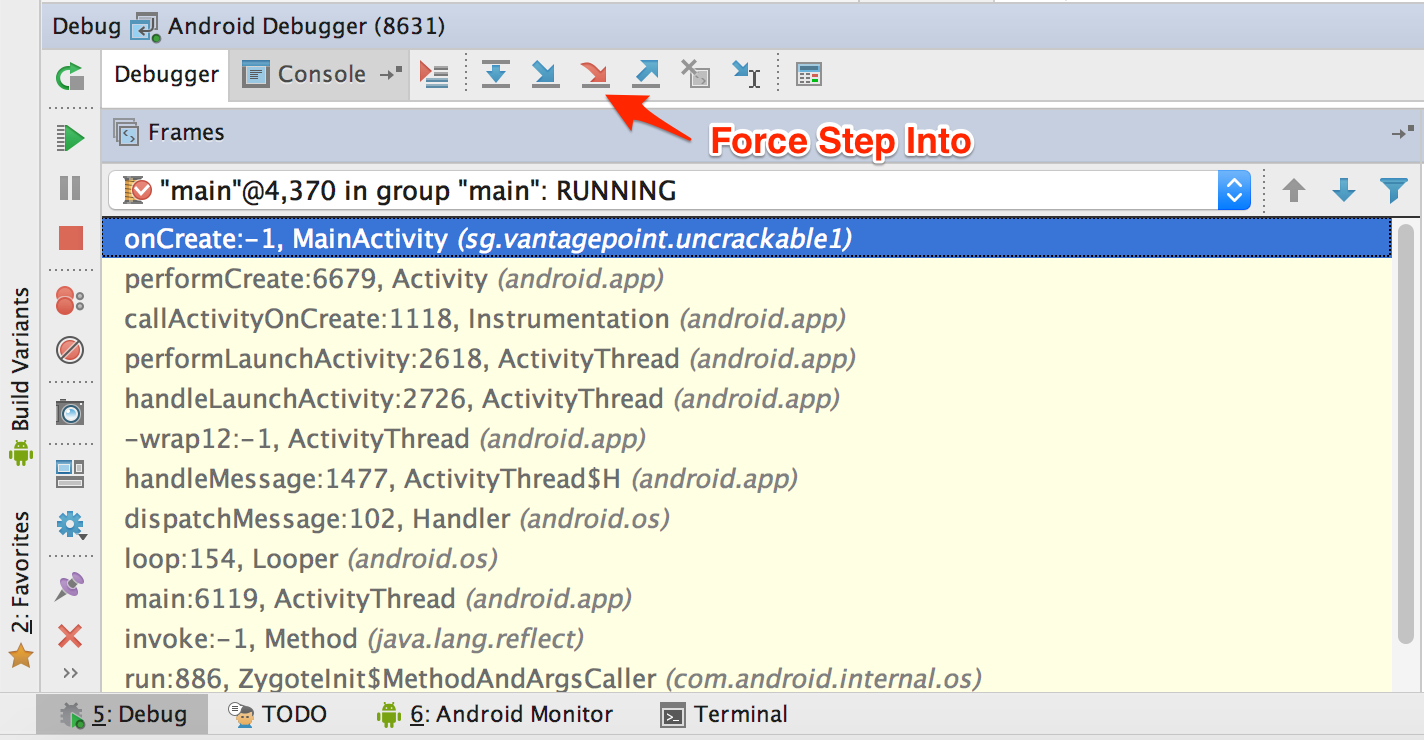

After you choose the Uncrackable1 application from the list, the debugger will attach to the app process and you will hit the breakpoint that was set on the onCreate() method. Uncrackable1 app triggers anti-debugging and anti-tampering controls within the onCreate() method. That's why it is a good idea to set a breakpoint on the onCreate() method just before the anti-tampering and anti-debugging checks performed.

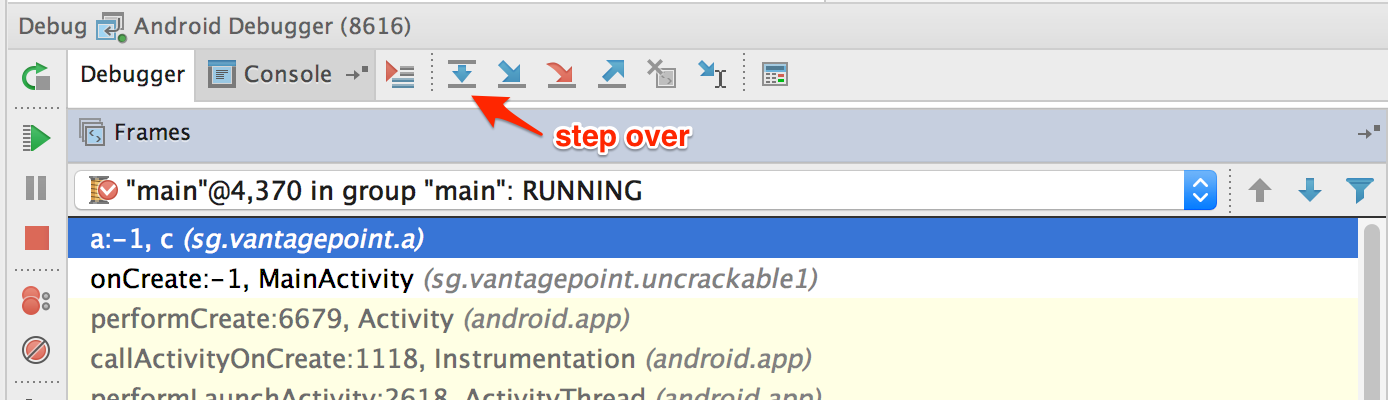

Next, we will single-step through the onCreate() method by clicking the "Force Step Into" button on the Debugger view. The "Force Step Into" option allows you to debug the Android framework functions and core Java classes that are normally ignored by debuggers.

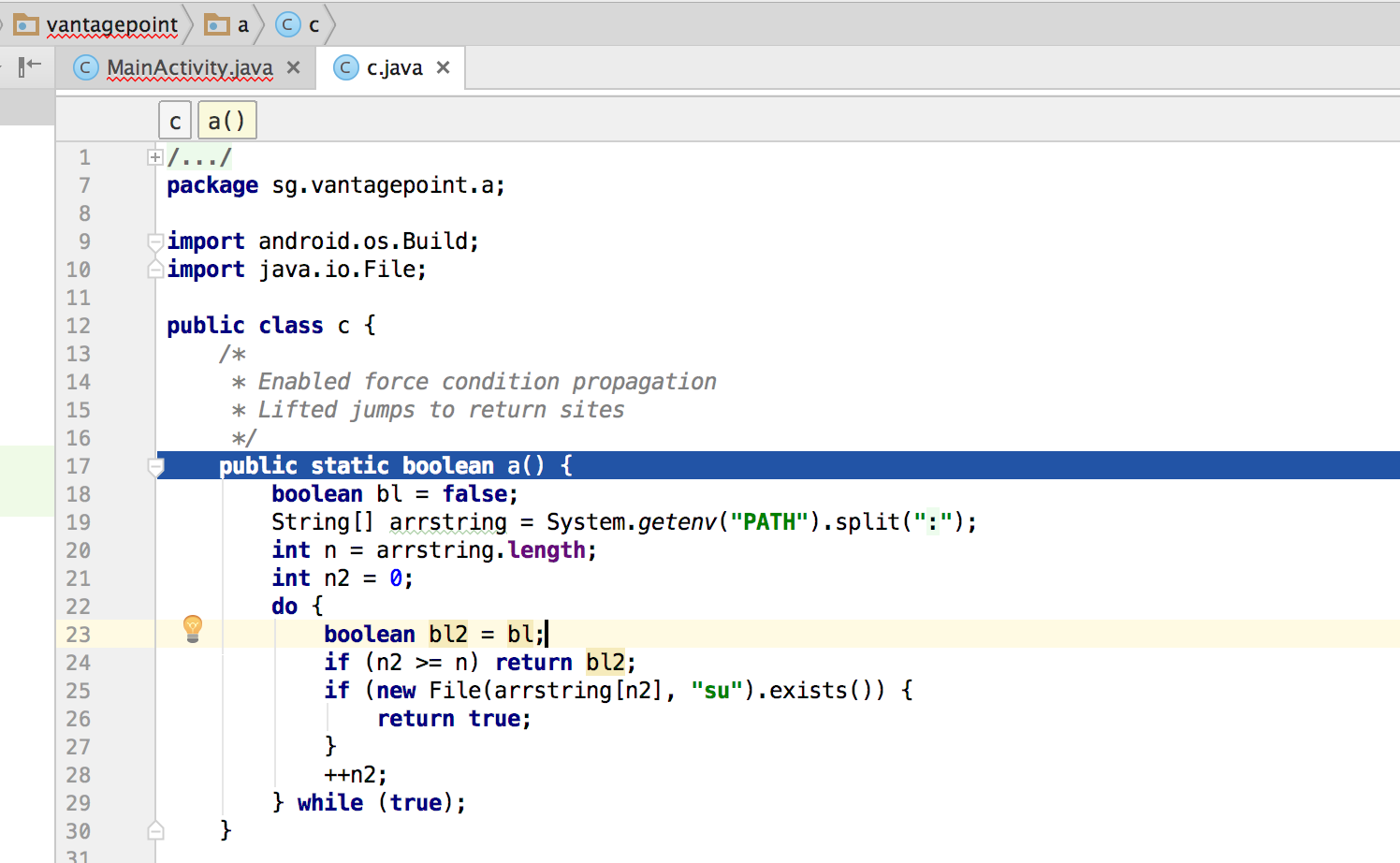

Once you "Force Step Into", the debugger will stop at the beginning of the next method which is the a() method of class sg.vantagepoint.a.c.

This method searches for "su" binary within well known directories. Since we are running the app on a rooted device/emulator we need to defeat this check by manipulating variables and/or function return values.

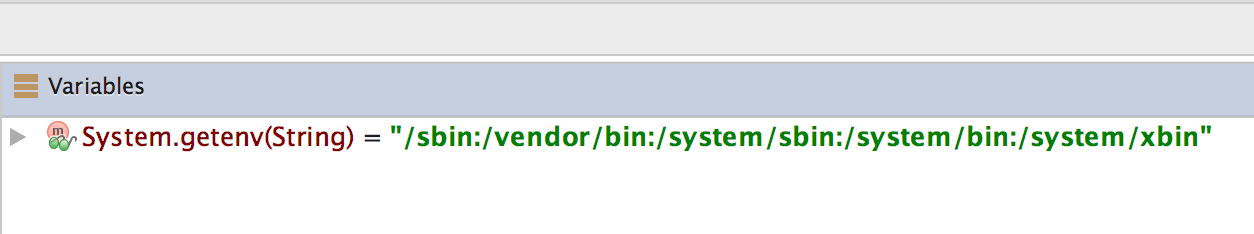

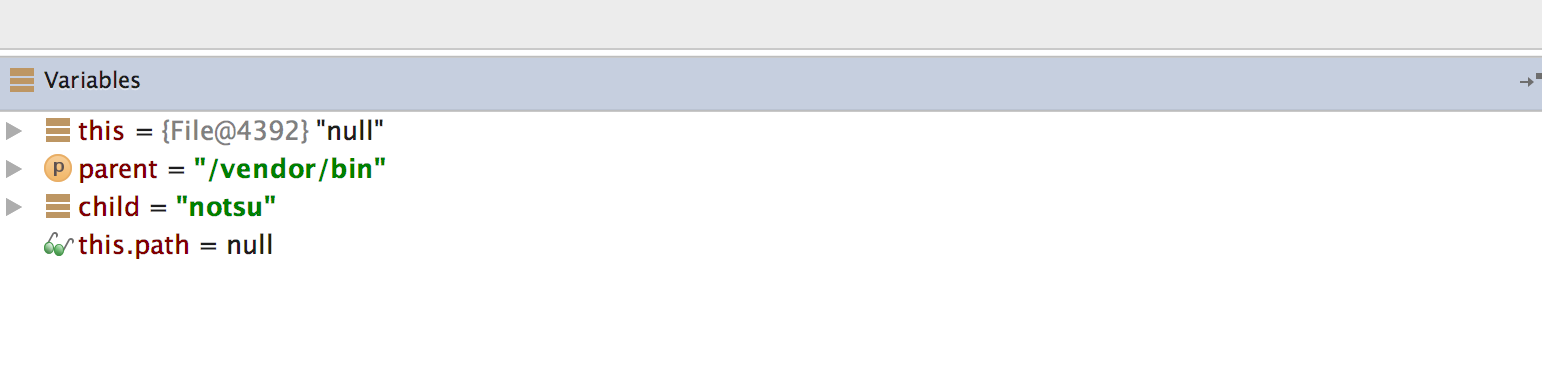

You can see the directory names inside the "Variables" window by stepping into the a() method and stepping through the method by clicking "Step Over" button in the Debugger view.

Step into the System.getenv method call y using the "Force Step Into" functionality.

After you get the colon separated directory names, the debugger cursor will return back to the beginning of a() method; not to the next executable line. This is just because we are working on the decompiled code insted of the original source code. So it is crucial for the analyst to follow the code flow while debugging decompiled applications. Othervise, it might get complicated to identify which line will be executed next.

If you don't want to debug core Java and Android classes, you can step out of the function by clicking "Step Out" button in the Debugger view. It might be a good approach to "Force Step Into" once you reach the decompiled sources and "Step Out" of the core Java and Android classes. This will help you to speed up your debugging while keeping eye on the return values of the core class functions.

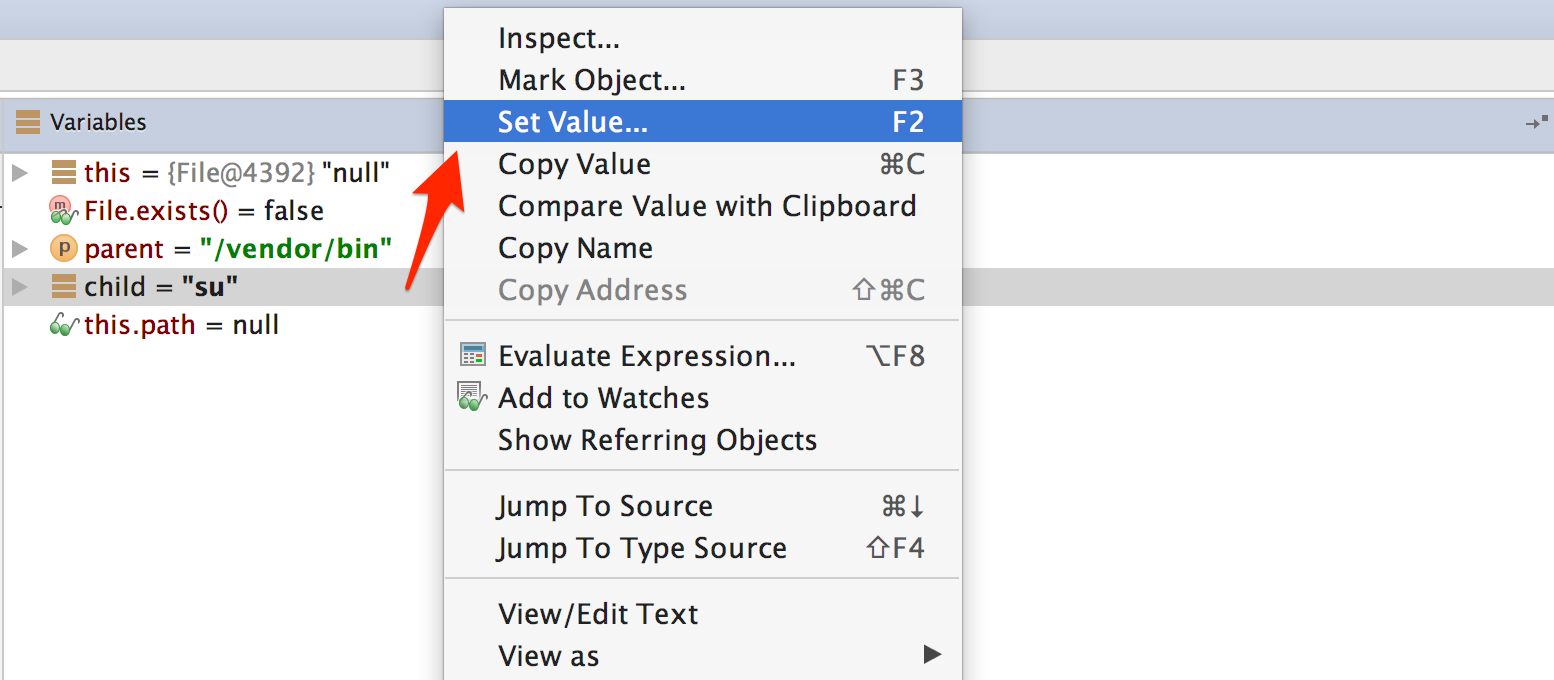

After it gets the directory names, a() method will search for the existence of the </code>su</code> binary within these directories. In order to defeat this control, you can modify the directory names (parent) or file name (child) at cycle which would otherwise detect the su binary on your device. You can modify the variable content by pressing F2 or Right-Click and "Set Value".

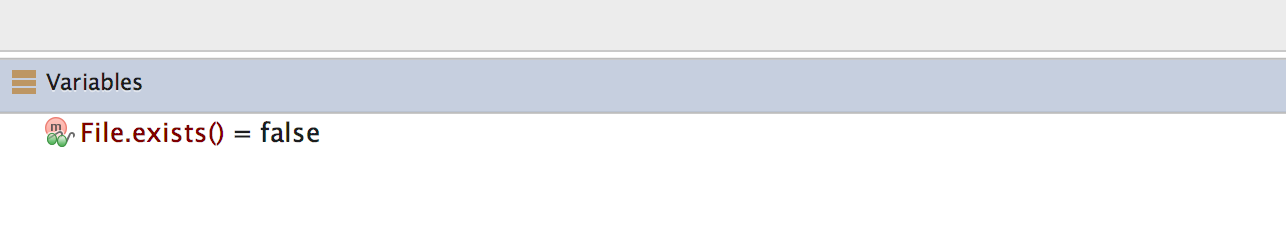

Once you modify the binary name or the directory name, File.exists should return false.

This defeats the first root detection control of Uncrackable App Level 1. The remaining anti-tampering and anti-debugging controls can be defeated in similar ways to finally reach secret string verification functionality.

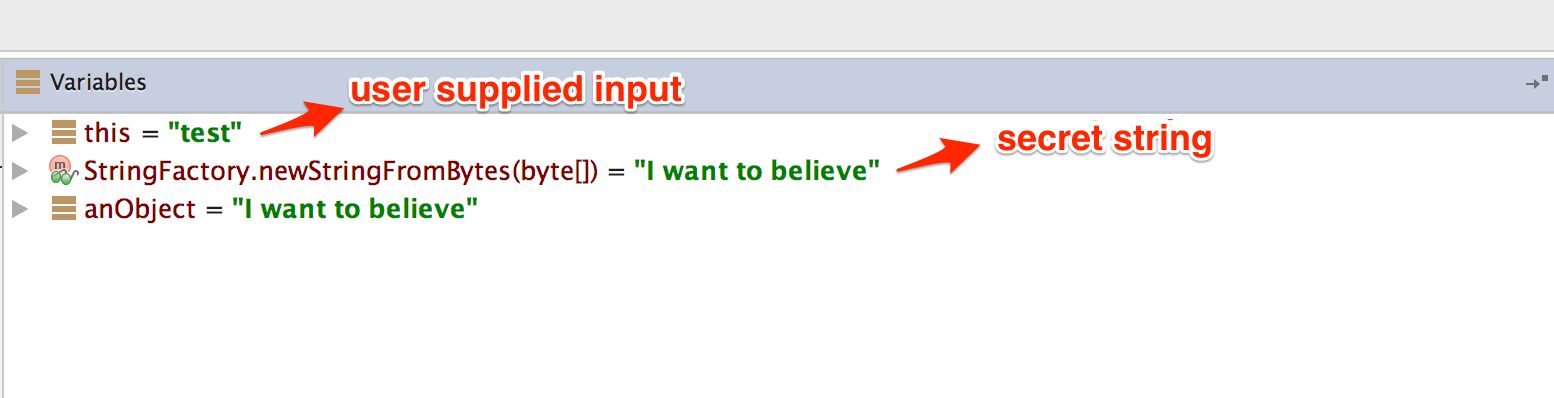

The secret code is verified by the method a() of class sg.vantagepoint.uncrackable1.a. Set a breakpoint on method a() and "Force Step Into" when you hit the breakpoint. Then, single-step until you reach the call to String.equals. This is where user supplied input is compared with the secret string.

You can see the secret string in the "Variables" view at the time you reach the String.equals method call.

Debugging Native Code

Native code on Android is packed into ELF shared libraries and runs just like any other native Linux program. Consequently, you can debug them using standard tools, including GDB and the built-in native debuggers of IDEs such as IDA Pro and JEB, as long as they support the processor architecture of the device (most devices are based on ARM chipsets, so this is usually not an issue).

We'll now set up our JNI demo app, HelloWorld-JNI.apk, for debugging. It's the same APK you downloaded in "Statically Analyzing Native Code". Use adb install to install it on your device or on an emulator.

$ adb install HelloWorld-JNI.apk

If you followed the instructions at the start of this chapter, you should already have the Android NDK. It contains prebuilt versions of gdbserver for various architectures. Copy the gdbserver binary to your device:

$ adb push $NDK/prebuilt/android-arm/gdbserver/gdbserver /data/local/tmp

The gdbserver --attach<comm> <pid> command causes gdbserver to attach to the running process and bind to the IP address and port specified in comm, which in our case is a HOST:PORT descriptor. Start HelloWorld-JNI on the device, then connect to the device and determine the PID of the HelloWorld process. Then, switch to the root user and attach gdbserver as follows.

$ adb shell

$ ps | grep helloworld

u0_a164 12690 201 1533400 51692 ffffffff 00000000 S sg.vantagepoint.helloworldjni

$ su

# /data/local/tmp/gdbserver --attach localhost:1234 12690

Attached; pid = 12690

Listening on port 1234

The process is now suspended, and gdbserver listening for debugging clients on port 1234. With the device connected via USB, you can forward this port to a local port on the host using the abd forward command:

$ adb forward tcp:1234 tcp:1234

We'll now use the prebuilt version of gdb contained in the NDK toolchain (if you haven't already, follow the instructions above to install it).

$ $TOOLCHAIN/bin/gdb libnative-lib.so

GNU gdb (GDB) 7.11

(...)

Reading symbols from libnative-lib.so...(no debugging symbols found)...done.

(gdb) target remote :1234

Remote debugging using :1234

0xb6e0f124 in ?? ()

We have successfully attached to the process! The only problem is that at this point, we're already too late to debug the JNI function StringFromJNI() as it only runs once at startup. We can again solve this problem by activating the "Wait for Debugger" option. Go to "Developer Options" -> "Select debug app" and pick HelloWorldJNI, then activate the "Wait for debugger" switch. Then, terminate and re-launch the app. It should be suspended automatically.

Our objective is to set a breakpoint at the start of the native function Java_sg_vantagepoint_helloworldjni_MainActivity_stringFromJNI() before resuming the app. Unfortunately, this isn't possible at this early point in execution because libnative-lib.so isn't yet mapped into process memory - it is loaded dynamically during runtime. To get this working, we'll first use JDB to gently control the process into the state we need.

First, we resume execution of the Java VM by attaching JDB. We don't want the process to resume immediately though, so we pipe the suspend command into JDB as follows:

$ adb jdwp

14342

$ adb forward tcp:7777 jdwp:14342

$ { echo "suspend"; cat; } | jdb -attach localhost:7777

Next, we want to suspend the process at the point the Java runtime loads libnative-lib.so. In JDB, set a breakpoint on the java.lang.System.loadLibrary() method and resume the process. After the breakpoint has been hit, execute the step up command, which will resume the process until loadLibrary()returns. At this point, libnative-lib.so has been loaded.

> stop in java.lang.System.loadLibrary

> resume

All threads resumed.

Breakpoint hit: "thread=main", java.lang.System.loadLibrary(), line=988 bci=0

> step up

main[1] step up

>

Step completed: "thread=main", sg.vantagepoint.helloworldjni.MainActivity.<clinit>(), line=12 bci=5

main[1]

Execute gdbserver to attach to the suspended app. This will have the effect that the app is "double-suspended" by both the Java VM and the Linux kernel.

$ adb forward tcp:1234 tcp:1234

$ $TOOLCHAIN/arm-linux-androideabi-gdb libnative-lib.so

GNU gdb (GDB) 7.7

Copyright (C) 2014 Free Software Foundation, Inc.

(...)

(gdb) target remote :1234

Remote debugging using :1234

0xb6de83b8 in ?? ()

Execute the resume command in JDB to resume execution of the Java runtime (we're done using JDB, so you can also detach it at this point). You can start exploring the process with GDB. The info sharedlibrary command displays the loaded libraries, which should include libnative-lib.so. The info functions command retrieves a list of all known functions. The JNI function java_sg_vantagepoint_helloworldjni_MainActivity_stringFromJNI() should be listed as a non-debugging symbol. Set a breakpoint at the address of that function and resume the process.

(gdb) info sharedlibrary

(...)

0xa3522e3c 0xa3523c90 Yes (*) libnative-lib.so

(gdb) info functions

All defined functions:

Non-debugging symbols:

0x00000e78 Java_sg_vantagepoint_helloworldjni_MainActivity_stringFromJNI

(...)

0xa3522e78 Java_sg_vantagepoint_helloworldjni_MainActivity_stringFromJNI

(...)

(gdb) b *0xa3522e78

Breakpoint 1 at 0xa3522e78

(gdb) cont

Your breakpoint should be hit when the first instruction of the JNI function is executed. You can now display a disassembly of the function using the disassemble command.

Breakpoint 1, 0xa3522e78 in Java_sg_vantagepoint_helloworldjni_MainActivity_stringFromJNI() from libnative-lib.so

(gdb) disass $pc

Dump of assembler code for function Java_sg_vantagepoint_helloworldjni_MainActivity_stringFromJNI:

=> 0xa3522e78 <+0>: ldr r2, [r0, #0]

0xa3522e7a <+2>: ldr r1, [pc, #8] ; (0xa3522e84 <Java_sg_vantagepoint_helloworldjni_MainActivity_stringFromJNI+12>)

0xa3522e7c <+4>: ldr.w r2, [r2, #668] ; 0x29c

0xa3522e80 <+8>: add r1, pc

0xa3522e82 <+10>: bx r2

0xa3522e84 <+12>: lsrs r4, r7, #28

0xa3522e86 <+14>: movs r0, r0

End of assembler dump.

From here on, you can single-step through the program, print the contents of registers and memory, or tamper with them, to explore the inner workings of the JNI function (which, in this case, simply returns a string). Use the help command to get more information on debugging, running and examining data.

Execution Tracing

Besides being useful for debugging, the JDB command line tool also offers basic execution tracing functionality. To trace an app right from the start we can pause the app using the Android "Wait for Debugger" feature or a kill –STOP command and attach JDB to set a deferred method breakpoint on an initialization method of our choice. Once the breakpoint hits, we activate method tracing with the trace go methods command and resume execution. JDB will dump all method entries and exits from that point on.

$ adb forward tcp:7777 jdwp:7288

$ { echo "suspend"; cat; } | jdb -attach localhost:7777

Set uncaught java.lang.Throwable

Set deferred uncaught java.lang.Throwable

Initializing jdb ...

> All threads suspended.

> stop in com.acme.bob.mobile.android.core.BobMobileApplication.<clinit>()

Deferring breakpoint com.acme.bob.mobile.android.core.BobMobileApplication.<clinit>().

It will be set after the class is loaded.

> resume

All threads resumed.M

Set deferred breakpoint com.acme.bob.mobile.android.core.BobMobileApplication.<clinit>()

Breakpoint hit: "thread=main", com.acme.bob.mobile.android.core.BobMobileApplication.<clinit>(), line=44 bci=0

main[1] trace go methods

main[1] resume

Method entered: All threads resumed.

The Dalvik Debug Monitor Server (DDMS) a GUI tool included with Android Studio. At first glance it might not look like much, but make no mistake: Its Java method tracer is one of the most awesome tools you can have in your arsenal, and is indispensable for analyzing obfuscated bytecode.

Using DDMS is a bit confusing however: It can be launched in several ways, and different trace viewers will be launched depending on how the trace was obtained. There’s a standalone tool called "Traceview" as well as a built-in viewer in Android Studio, both of which offer different ways of navigating the trace. You’ll usually want to use the viewer built into Android studio which gives you a nice, zoom-able hierarchical timeline of all method calls. The standalone tool however is also useful, as it has a profile panel that shows the time spent in each method, as well as the parents and children of each method.

To record an execution trace in Android studio, open the "Android" tab at the bottom of the GUI. Select the target process in the list and the click the little “stop watch” button on the left. This starts the recording. Once you are done, click the same button to stop the recording. The integrated trace view will open showing the recorded trace. You can scroll and zoom the timeline view using the mouse or trackpad.

Alternatively, execution traces can also be recorded in the standalone Android Device Monitor. The Device Monitor can be started from within Android Studo (Tools -> Android -> Android Device Monitor) or from the shell with the ddms command.

To start recording tracing information, select the target process in the "Devices" tab and click the “Start Method Profiling” button. Click the stop button to stop recording, after which the Traceview tool will open showing the recorded trace. An interesting feature of the standalone tool is the "profile" panel on the bottom, which shows an overview of the time spent in each method, as well as each method’s parents and children. Clicking any of the methods in the profile panel highlights the selected method in the timeline panel.

As an aside, DDMS also offers convenient heap dump button that will dump the Java heap of a process to a .hprof file. More information on Traceview can be found in the Android Studio user guide.

Tracing System Calls

Moving down a level in the OS hierarchy, we arrive at privileged functions that require the powers of the Linux kernel. These functions are available to normal processes via the system call interface. Instrumenting and intercepting calls into the kernel is an effective method to get a rough idea of what a user process is doing, and is often the most efficient way to deactivate low-level tampering defenses.

Strace is a standard Linux utility that is used to monitor interaction between processes and the kernel. The utility is not included with Android by default, but can be easily built from source using the Android NDK. This gives us a very convenient way of monitoring system calls of a process. Strace however depends on the ptrace() system call to attach to the target process, so it only works up to the point that anti-debugging measures kick in.

As a side note, if the Android "stop application at startup: feature is unavailable we can use a shell script to make sure that strace attached immediately once the process is launched (not an elegant solution but it works):

$ while true; do pid=$(pgrep 'target_process' | head -1); if [[ -n "$pid" ]]; then strace -s 2000 - e “!read” -ff -p "$pid"; break; fi; done

Ftrace

Ftrace is a tracing utility built directly into the Linux kernel. On a rooted device, ftrace can be used to trace kernel system calls in a more transparent way than is possible with strace, which relies on the ptrace system call to attach to the target process.

Conveniently, ftrace functionality is found in the stock Android kernel on both Lollipop and Marshmallow. It can be enabled with the following command:

$ echo 1 > /proc/sys/kernel/ftrace_enabled

The /sys/kernel/debug/tracing directory holds all control and output files and related to ftrace. The following files are found in this directory:

- available_tracers: This file lists the available tracers compiled into the kernel.

- current_tracer: This file is used to set or display the current tracer.

- tracing_on: Echo 1 into this file to allow/start update of the ring buffer. Echoing 0 will prevent further writes into the ring buffer.

KProbes

The KProbes interface provides us with an even more powerful way to instrument the kernel: It allows us to insert probes into (almost) arbitrary code addresses within kernel memory. Kprobes work by inserting a breakpoint instruction at the specified address. Once the breakpoint is hit, control passes to the Kprobes system, which then executes the handler function(s) defined by the user as well as the original instruction. Besides being great for function tracing, KProbes can be used to implement rootkit-like functionality such as file hiding.

Jprobes and Kretprobes are additional probe types based on Kprobes that allow hooking of function entries and exits.

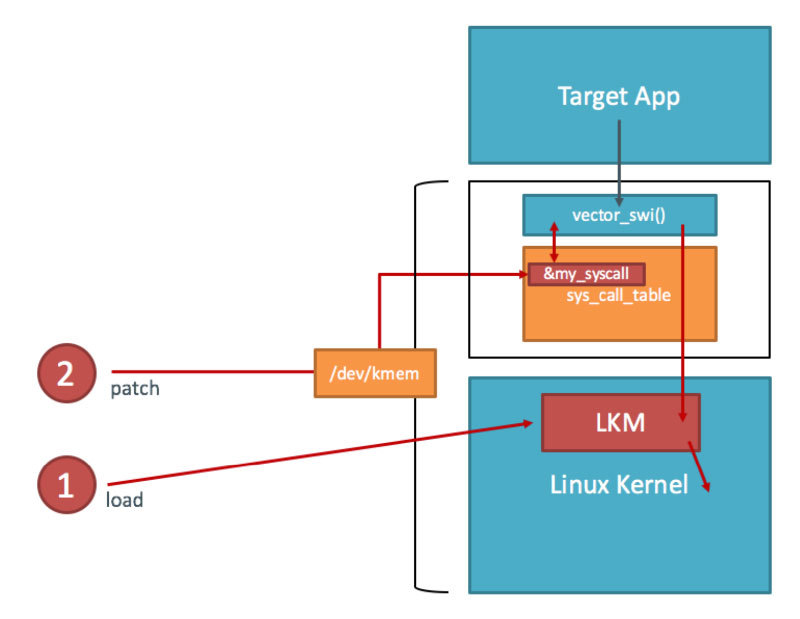

Unfortunately, the stock Android kernel comes without loadable module support, which is a problem given that Kprobes are usually deployed as kernel modules. Another issue is that the Android kernel is compiled with strict memory protection which prevents patching some parts of Kernel memory. Using Elfmaster’s system call hooking method [16]</code> results in a Kernel panic on default Lolllipop and Marshmallow due to sys_call_table being non-writable. We can however use Kprobes on a sandbox by compiling our own, more lenient Kernel (more on this later).

Emulation-based Analysis

Even in its standard form that ships with the Android SDK, the Android emulator – a.k.a. “emulator” - is a somewhat capable reverse engineering tool. It is based on QEMU, a generic and open source machine emulator. QEMU emulates a guest CPU by translating the guest instructions on-the-fly into instructions the host processor can understand. Each basic block of guest instructions is disassembled and translated into an intermediate representation called Tiny Code Generator (TCG). The TCG block is compiled into a block of host instructions, stored into a code cache, and executed. After execution of the basic block has completed, QEMU repeats the process for the next block of guest instructions (or loads the already translated block from the cache). The whole process is called dynamic binary translation.

Because the Android emulator is a fork of QEMU, it comes with the full QEMU feature set, including its monitoring, debugging and tracing facilities. QEMU-specific parameters can be passed to the emulator with the -qemu command line flag. We can use QEMU’s built-in tracing facilities to log executed instructions and virtual register values. Simply starting qemu with the "-d" command line flag will cause it to dump the blocks of guest code, micro operations or host instructions being executed. The –d in_asm option logs all basic blocks of guest code as they enter QEMU’s translation function. The following command logs all translated blocks to a file:

$ emulator -show-kernel -avd Nexus_4_API_19 -snapshot default-boot -no-snapshot-save -qemu -d in_asm,cpu 2>/tmp/qemu.log

Unfortunately, it is not possible to generate a complete guest instruction trace with QEMU, because code blocks are written to the log only at the time they are translated – not when they’re taken from the cache. For example, if a block is repeatedly executed in a loop, only the first iteration will be printed to the log. There’s no way to disable TB caching in QEMU (save for hacking the source code). Even so, the functionality is sufficient for basic tasks, such as reconstructing the disassembly of a natively executed cryptographic algorithm.

Dynamic analysis frameworks, such as PANDA and DroidScope, build on QEMU to provide more complete tracing functionality. PANDA/PANDROID is your best if you’re going for a CPU-trace based analysis, as it allows you to easily record and replay a full trace, and is relatively easy to set up if you follow the build instructions for Ubuntu.

DroidScope

DroidScope - an extension to the DECAF dynamic analysis framework [20] - is a malware analysis engine based on QEMU. It adds instrumentation on several levels, making it possible to fully reconstruct the semantics on the hardware, Linux and Java level.

DroidScope exports instrumentation APIs that mirror the different context levels (hardware, OS and Java) of a real Android device. Analysis tools can use these APIs to query or set information and register callbacks for various events. For example, a plugin can register callbacks for native instruction start and end, memory reads and writes, register reads and writes, system calls or Java method calls.

All of this makes it possible to build tracers that are practically transparent to the target application (as long as we can hide the fact it is running in an emulator). One limitation is that DroidScope is compatible with the Dalvik VM only.

PANDA

PANDA [21] is another QEMU-based dynamic analysis platform. Similar to DroidScope, PANDA can be extended by registering callbacks that are triggered upon certain QEMU events. The twist PANDA adds is its record/replay feature. This allows for an iterative workflow: The reverse engineer records an execution trace of some the target app (or some part of it) and then replays it over and over again, refining his analysis plugins with each iteration.

PANDA comes with some pre-made plugins, such as a stringsearch tool and a syscall tracer. Most importantly, it also supports Android guests and some of the DroidScope code has even been ported over. Building and running PANDA for Android (“PANDROID”) is relatively straightforward. To test it, clone Moiyx’s git repository and build PANDA as follows:

$ cd qemu

$ ./configure --target-list=arm-softmmu --enable-android $ makee

As of this writing, Android versions up to 4.4.1 run fine in PANDROID, but anything newer than that won’t boot. Also, the Java level introspection code only works on the specific Dalvik runtime of Android 2.3. Anyways, older versions of Android seem to run much faster in the emulator, so if you plan on using PANDA sticking with Gingerbread is probably best. For more information, check out the extensive documentation in the PANDA git repo.

VxStripper

Another very useful tool built on QEMU is VxStripper by Sébastien Josse [22]. VXStripper is specifically designed for de-obfuscating binaries. By instrumenting QEMU's dynamic binary translation mechanisms, it dynamically extracts an intermediate representation of a binary. It then applies simplifications to the extracted intermediate representation, and recompiles the simplified binary using LLVM. This is a very powerful way of normalizing obfuscated programs. See Sébastien's paper [23] for more information.

Tampering and Runtime Instrumentation

First, we'll look at some simple ways of modifying and instrumenting mobile apps. Tampering means making patches or runtime changes to the app to affect its behavior - usually in a way that's to our advantage. For example, it could be desirable to deactivate SSL pinning or deactivate binary protections that hinder the testing process. Runtime Instrumentation encompasses adding hooks and runtime patches to observe the app's behavior. In mobile app-sec however, the term is used rather loosely to refer to all kinds runtime manipulation, including overriding methods to change behavior.

Patching and Re-Packaging

Making small changes to the app Manifest or bytecode is often the quickest way to fix small annoyances that prevent you from testing or reverse engineering an app. On Android, two issues in particular pop up regularly:

- You can't attach a debugger to the app because the android:debuggable flag is not set to true in the Manifest;

- You cannot intercept HTTPS traffic with a proxy because the app empoys SSL pinning.

In most cases, both issues can be fixed by making minor changes and re-packaging and re-signing the app (the exception are apps that run additional integrity checks beyond default Android code signing - in theses cases, you also have to patch out those additional checks as well).

Example: Disabling SSL Pinning

Certificate pinning is an issue for security testers who want to intercepts HTTPS communication for legitimate reasons. To help with this problem, the bytecode can be patched to deactivate SSL pinning. To demonstrate how Certificate Pinning can be bypassed, we will walk through the necessary steps to bypass Certificate Pinning implemented in an example application.

The first step is to disassemble the APK with apktool:

$ apktool d target_apk.apk

You then need to locate the certificate pinning checks in the Smali source code. Searching the smali code for keywords such as “X509TrustManager” should point you in the right direction.

In our example, a search for "X509TrustManager" returns one class that implements a custom Trustmanager. The derived class implements methods named checkClientTrusted, checkServerTrusted and getAcceptedIssuers.

Insert the return-void opcode was added to the first line of each of these methods to bypass execution. This causes each method to return immediately. return value. With this modification, no certificate checks are performed, and the application will accept all certificates.

.method public checkServerTrusted([LJava/security/cert/X509Certificate;Ljava/lang/String;)V

.locals 3

.param p1, "chain" # [Ljava/security/cert/X509Certificate;

.param p2, "authType" # Ljava/lang/String;

.prologue

return-void # <-- OUR INSERTED OPCODE!

.line 102

iget-object v1, p0, Lasdf/t$a;->a:Ljava/util/ArrayList;

invoke-virtual {v1}, Ljava/util/ArrayList;->iterator()Ljava/util/Iterator;

move-result-object v1

:goto_0

invoke-interface {v1}, Ljava/util/Iterator;->hasNext()Z

Hooking Java Methods with Xposed

Xposed is a "framework for modules that can change the behavior of the system and apps without touching any APKs" [24]. Technically, it is an extended version of Zygote that exports APIs for running Java code when a new process is started. By running Java code in the context of the newly instantiated app, it is possible to resolve, hook and override Java methods belonging to the app. Xposed uses reflection to examine and modify the running app. Changes are applied in memory and persist only during the runtime of the process - no patches to the application files are made.

To use Xposed, you first need to install the Xposed framework on a rooted device. Modifications are then deployed in the form of separate apps ("modules") that can be toggled on and off in the Xposed GUI.

Example: Bypassing Root Detection with XPosed

Let's assume you're testing an app that is stubbornly quitting on your rooted device. You decompile the app and find the following highly suspect method:

package com.example.a.b

public static boolean c() {

int v3 = 0;

boolean v0 = false;

String[] v1 = new String[]{"/sbin/", "/system/bin/", "/system/xbin/", "/data/local/xbin/",

"/data/local/bin/", "/system/sd/xbin/", "/system/bin/failsafe/", "/data/local/"};

int v2 = v1.length;

for(int v3 = 0; v3 < v2; v3++) {

if(new File(String.valueOf(v1[v3]) + "su").exists()) {

v0 = true;

return v0;

}

}

return v0;

}

This method iterates through a list of directories, and returns "true" (device rooted) if the su binary is found in any of them. Checks like this are easy to deactivate - all you have to do is to replace the code with something that returns "false". Methok hooking using an Xposed module is one way to do this.

This method XposedHelpers.findAndHookMethodfindAndHookMethod allows you to override existing class methods. From the decompiled code, we know that the method performing the check is called c() and located in the class com.example.a.b. An Xposed module that overrides the function to always return "false" looks as follows.

package com.awesome.pentestcompany;

import static de.robv.android.xposed.XposedHelpers.findAndHookMethod;

import de.robv.android.xposed.IXposedHookLoadPackage;

import de.robv.android.xposed.XposedBridge;

import de.robv.android.xposed.XC_MethodHook;

import de.robv.android.xposed.callbacks.XC_LoadPackage.LoadPackageParam;

public class DisableRootCheck implements IXposedHookLoadPackage {

public void handleLoadPackage(final LoadPackageParam lpparam) throws Throwable {

if (!lpparam.packageName.equals("com.example.targetapp"))

return;

findAndHookMethod("com.example.a.b", lpparam.classLoader, "c", new XC_MethodHook() {

@Override

protected void beforeHookedMethod(MethodHookParam param) throws Throwable {

XposedBridge.log("Caught root check!");

param.setResult(false);

}

});

}

}

Modules for Xposed are developed and deployed with Android Studio just like regular Android apps. For more details on writing compiling and installing Xposed modules, refer to the tutorial provided by its author, rovo89 [24].

Dynamic Instrumentation with FRIDA

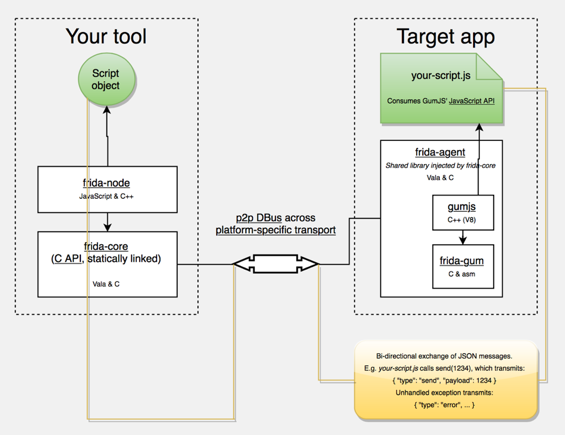

Frida "lets you inject snippets of JavaScript or your own library into native apps on Windows, macOS, Linux, iOS, Android, and QNX" [26]. While it was originally based on Google’s V8 Javascript runtime, since version 9 Frida now uses Duktape internally.

Code injection can be achieved in different ways. For example, Xposed makes some permanent modifications to the Android app loader that provide hooks to run your own code every time a new process is started. In contrast, Frida achieves code injection by writing code directly into process memory. The process is outlined in a bit more detail below.

When you "attach" Frida to a running app, it uses ptrace to hijack a thread in a running process. This thread is used to allocate a chunk of memory and populate it with a mini-bootstrapper. The bootstrapper starts a fresh thread, connects to the Frida debugging server running on the device, and loads a dynamically generated library file containing the Frida agent and instrumentation code. The original, hijacked thread is restored to its original state and resumed, and execution of the process continues as usual.

Frida injects a complete JavaScript runtime into the process, along with a powerful API that provides a wealth of useful functionality, including calling and hooking of native functions and injecting structured data into memory. It also supports interaction with the Android Java runtime, such as interacting with objects inside the VM.

FRIDA Architecture, source: http://www.frida.re/docs/hacking/

Here are some more APIs FRIDA offers on Android:

- Instantiate Java objects and call static and non-static class methods;

- Replace Java method implementations;

- Enumerate live instances of specific classes by scanning the Java heap (Dalvik only);

- Scan process memory for occurrences of a string;

- Intercept native function calls to run your own code at function entry and exit.

Some features unfortunately don’t work yet on current Android devices platforms. Most notably, the FRIDA Stalker - a code tracing engine based on dynamic recompilation - does not support ARM at the time of this writing (version 7.2.0). Also, support for ART has been included only recently, so the Dalvik runtime is still better supported.

Installing Frida

To install Frida locally, simply use Pypi:

$ sudo pip install frida

Your Android device doesn't need to be rooted to get Frida running, but it's the easiest setup and we assume a rooted device here unless noted otherwise. Download the frida-server binary from the Frida releases page. Make sure that the server version (at least the major version number) matches the version of your local Frida installation. Usually, Pypi will install the latest version of Frida, but if you are not sure, you can check with the Frida command line tool:

$ frida --version

9.1.10

$ wget https://github.com/frida/frida/releases/download/9.1.10/frida-server-9.1.10-android-arm.xz

Copy frida-server to the device and run it:

$ adb push frida-server /data/local/tmp/

$ adb shell "chmod 755 /data/local/tmp/frida-server"

$ adb shell "su -c /data/local/tmp/frida-server &"

With frida-server running, you should now be able to get a list of running processes with the following command:

$ frida-ps -U

PID Name

----- --------------------------------------------------------------

276 adbd

956 android.process.media

198 bridgemgrd

1191 com.android.nfc

1236 com.android.phone

5353 com.android.settings

936 com.android.systemui

(...)

The -U option lets Frida search for USB devices or emulators.

To trace specific (low level) library calls, you can use the frida-trace command line tool:

frida-trace -i "open" -U com.android.chrome

This generates a little javascript in __handlers__/libc.so/open.js that Frida injects into the process and that traces all calls to the open function in libc.so. You can modify the generated script according to your needs, making use of Fridas Javascript API.

To work with Frida interactively, you can use frida CLI which hooks into a process and gives you a command line interface to Frida's API.

frida -U com.android.chrome

You can also use frida CLI to load scripts via the -l option, e.g to load myscript.js:

frida -U -l myscript.js com.android.chrome

Frida also provides a Java API which is especially helpful for dealing with Android apps. It lets you work with Java classes and objects directly. This is a script to overwrite the "onResume" function of an Activity class:

Java.perform(function () {

var Activity = Java.use("android.app.Activity");

Activity.onResume.implementation = function () {

console.log("[*] onResume() got called!");

this.onResume();

};

});

The script above calls Java.perform to make sure that our code gets executed in the context of the Java VM. It instantiates a wrapper for the android.app.Activity class via Java.use and overwrites the onResume function. The new onResume function outputs a notice to the console and calls the original onResume method by invoking this.onResume every time an activity is resumed in the the app.

Frida also lets you search for instantiated objects on the heap and work with them. The following script searches for instances of android.view.View objects and calls their toString method. The result is printed to the console:

setImmediate(function() {

console.log("[*] Starting script");

Java.perform(function () {

Java.choose("android.view.View", {

"onMatch":function(instance){

console.log("[*] Instance found: " + instance.toString());

},

"onComplete":function() {

console.log("[*] Finished heap search")

}

});

});

});

The output would look like this:

[*] Starting script

[*] Instance found: android.view.View{7ccea78 G.ED..... ......ID 0,0-0,0 #7f0c01fc app:id/action_bar_black_background}

[*] Instance found: android.view.View{2809551 V.ED..... ........ 0,1731-0,1731 #7f0c01ff app:id/menu_anchor_stub}

[*] Instance found: android.view.View{be471b6 G.ED..... ......I. 0,0-0,0 #7f0c01f5 app:id/location_bar_verbose_status_separator}

[*] Instance found: android.view.View{3ae0eb7 V.ED..... ........ 0,0-1080,63 #102002f android:id/statusBarBackground}

[*] Finished heap search

Notice that you can also make use of Java's reflection capabilities. To list the public methods of the android.view.View class you could create a wrapper for this class in Frida and call getMethods() from its class property:

Java.perform(function () {

var view = Java.use("android.view.View");

var methods = view.class.getMethods();

for(var i = 0; i < methods.length; i++) {

console.log(methods[i].toString());

}

});

Besides loading scripts via frida CLI, Frida also provides Python, C, NodeJS, Swift and various other bindings.

Solving the OWASP Uncrackable Crackme Level1 with Frida

Frida gives you the possibility to solve the OWASP UnCrackable Crackme Level 1 easily. We have already seen that we can hook method calls with Frida above.

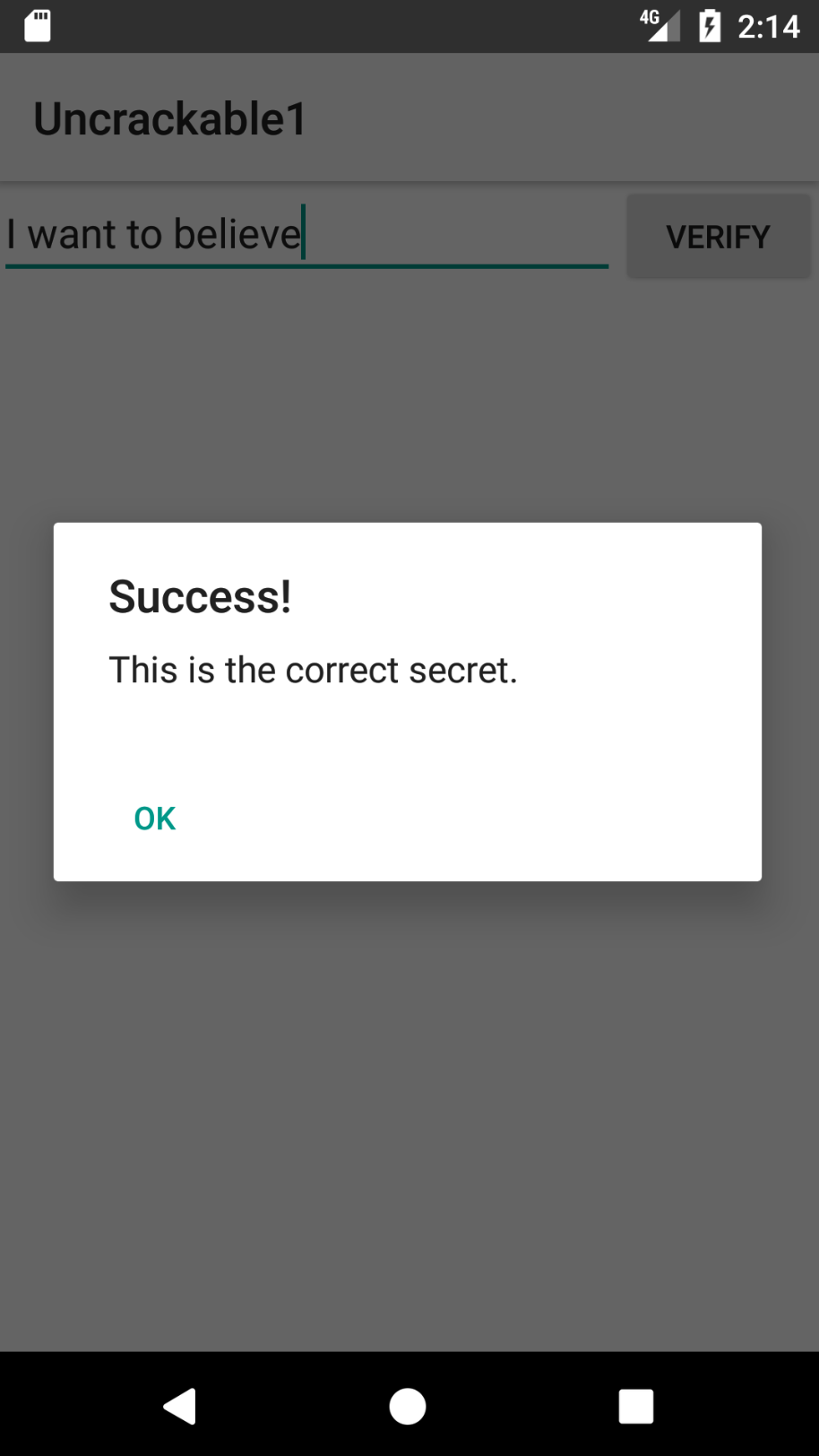

When you start the App on an emulator or a rooted device, you find that the app presents a dialog box and exits as soon as you press "Ok" because it detected root:

Let us see how we can prevent this. The decompiled main method (using CFR decompiler) looks like this:

package sg.vantagepoint.uncrackable1;

import android.app.Activity;

import android.app.AlertDialog;

import android.content.Context;

import android.content.DialogInterface;

import android.os.Bundle;

import android.text.Editable;

import android.view.View;

import android.widget.EditText;

import sg.vantagepoint.uncrackable1.a;

import sg.vantagepoint.uncrackable1.b;

import sg.vantagepoint.uncrackable1.c;

public class MainActivity

extends Activity {

private void a(String string) {

AlertDialog alertDialog = new AlertDialog.Builder((Context)this).create();

alertDialog.setTitle((CharSequence)string);

alertDialog.setMessage((CharSequence)"This in unacceptable. The app is now going to exit.");

alertDialog.setButton(-3, (CharSequence)"OK", (DialogInterface.OnClickListener)new b(this));

alertDialog.show();

}

protected void onCreate(Bundle bundle) {

if (sg.vantagepoint.a.c.a() || sg.vantagepoint.a.c.b() || sg.vantagepoint.a.c.c()) {

this.a("Root detected!"); //This is the message we are looking for

}

if (sg.vantagepoint.a.b.a((Context)this.getApplicationContext())) {

this.a("App is debuggable!");

}

super.onCreate(bundle);

this.setContentView(2130903040);

}

public void verify(View object) {

object = ((EditText)this.findViewById(2131230720)).getText().toString();

AlertDialog alertDialog = new AlertDialog.Builder((Context)this).create();

if (a.a((String)object)) {

alertDialog.setTitle((CharSequence)"Success!");

alertDialog.setMessage((CharSequence)"This is the correct secret.");

} else {

alertDialog.setTitle((CharSequence)"Nope...");

alertDialog.setMessage((CharSequence)"That's not it. Try again.");

}

alertDialog.setButton(-3, (CharSequence)"OK", (DialogInterface.OnClickListener)new c(this));

alertDialog.show();

}

}